Rurals of Nevada: Native Communities in the Three Rurals (art. 12)

"Reservations are . . . remnants of our homelands that have been reserved for our use and for us to live on. So these weren't given to us." - David Treuer, NPR Talk of the Nation, 2012

Last week’s admittedly overly-long installment on the problems with how Native American communities are seen by policymakers with overlapping definitions and geographies covered many of the themes I will continue in this article. I do want to spend this week talking a bit more about the data. I promise.

A couple of comments before starting. First, the data below will be pulled mostly from the 2020 Census, namely the P.L. 94-171 Re-Districting File. Given the relatively small size of Native American populations in the rurals, the American Community Surveys will be less generally useful (as I discussed in the first “Aging Rurals” article). In addition, the term “AIAN” below means anyone who selected American Indian / Alaska Native alone or in any combination. Finally, for simplicity, when I use the term “reservation” I mean all resident reservations and colonies. The Timbisha Shoshone and Fort Mojave areas would generally be excluded since they contain no resident population (although both certainly have members living elsewhere in the state). Summit Lake is included, although most of the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe lives in the Reno-Sparks area due to the remoteness and lack of services on the reservation (located in Humboldt County).

I want to begin by touching on an issue I brought up briefly at the end of last week’s article: the question of reservations. While widely considered the primary indigenous population centers, a small percentage actually lives on reservations—just 7.3% of the AIAN population in Nevada as of the 2020 Census. This fact may seem surprising, but failure to appreciate its significance. If a policymaker just looks at the reservation population, they are far more likely to conclude that the indigenous population is smaller than it is. This leads to serious misconceptions, such as the tendency to "speak about Native Americans in the past tense,” as Levi Rickert argued in a recent Native News Online article. Exploring the relationship between reservation and off-reservation populations can help understand where these fallacies are originating.

Of course, there are sharp differences between urban and rural areas. The three urban counties—Clark, Washoe, and Carson City—contain only 6 of Nevada’s 25 residential reservations (counting following the Census policy of dividing Fallon and Yerington into two reservations each). However, these include some of the largest reservations in Nevada by population and land area, and collectively reservation land comprises almost 6% of the acreage in the three urban counties, inclusive of the Fort Mojave holdings in Clark County (all land area data is from this excellent factsheet from the Lincy Institute, and Brookings Mountain West at UNLV). Washoe County contains over a third of Nevada’s tribal lands, mostly in the Pyramid Lake Reservation. The Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe is the largest single reservation population and is also one of the largest of Nevada’s indigenous tribes in terms of membership.

But only 3.3% of the AIAN population in these urban counties live on reservations. In part, this low number is due to a large number of non-Nevada AIAN populations in urban areas, as I discussed in the first article. We will know more when the fuller 2020 Census data is released this summer. Some of this population stems from earlier programs such as the ill-conceived and -implemented 1952-1972 Voluntary Relocation Plan for American Indians (excellent summary on this travesty here).

But it also reflects two other factors for both Nevada and non-Nevadan tribal communities. The first is the lack of housing and associated infrastructure on reservations, leaving many to seek housing elsewhere. The second is the lack of economic opportunity, which forces many adults to seek work in urban areas—which often leads to the necessity of living in these urban areas. Groups ranging from the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) to the National Low Income Housing Coalition have been tracking the interplay of these issues for years.

Even if they want too, many tribal members cannot live on reservations. This fact creates policy problems for both tribal and non-tribal governments which are only now starting to be addressed.

In other words, even if many indigenous peoples would like to live on reservations, there are many limits to doing so. And this creates some real policy dilemmas since members of Native American nations are not minorities, but members of sovereign states within the U.S. Many services for tribal communities are centered on the reservations and the complicated history of tribal-federal relations (from “ward” status to government-to-government) has left the impression for many policymakers at the state, county, and municipality levels that reservation issues are “not my problem.”

Yet given the large number of tribal members required for one reason or another to live off the reservation, it certainly is the problem of non-federal governments. As Matthew L. M. Fletcher argued in a 2017 American Indian Law Review article, states and counties are increasingly being confronted with the obligation to provide services they formerly (and incorrectly) assumed were federal responsibilities. As Ojibwe author David Treuer (Rez Life: An Indian’s Journey Through Reservation Life, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee, and others) noted in an NPR interview: “Our rights extend to the reservation, but they also extend oftentimes beyond the borders of the reservations.”

To really see the interplay between reservations and other communities, we should look at the areas where the reservations are most common. That would be the Rurals of Nevada.

Native Americans in the Three Rurals

Although only 17.4% of those Nevadans self-identifying in some measure as American Indian / Alaska Native (AIAN) live in the 14 rural counties, this is far larger than the percentage of other population groups. Remember from the first article that less than 10% of Nevada’s population lives in rural counties. Those who identify as “White Alone” have 13.9% of their population in the rurals, but rural residents comprise well less than 6% of all other racial and ethnic groups, including Hispanic/Latinos. Collectively, the AIAN population comprises 6.3% of the total rural population—a little less than double the percentage in Nevada as a whole.

This may seem unsurprising given that Nevada’s rurals also have the largest number of reservations. Of Nevada’s 26 reservations with resident populations, 19 are in the rurals. Almost half—9 of the 19—are located in the I-80 Corridor counties of Elko, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing (Eureka County has no reservation in-county). Both the Western Rural and Central Rural regions have five each: in Douglas, Lyon, and Churchill Counties for the Western Rural and in Mineral (although Walker River Reservation has some land in both Lyon and Churchill Counties), Nye, and White Pine in the Central Rural. Like Eureka, Esmeralda, Lincoln, and Storey Counties have no reservations or colonies—although they certainly have AIAN populations.

Collectively, these populations have recognized jurisdiction over a little more than 1% of Nevada’s rural land area—although that represents over half of Nevada’s tribal lands (56.3%). Over a quarter of all tribal land is in the Central Rural region (mostly the Walker River Reservation), although the population base here is small. The other two rural regions have between 15% and 16% of the total tribal land each. Interestingly, Douglas County has the largest percentage of tribal land, with 17.6% of the county under tribal jurisdiction (for comparison, Walker River Reservation contains just over 11% of Mineral County’s land area).

So, we have another situation where the Three Rurals differ quite a bit from each other. Below is a chart summarizing the breakdown of the AIAN population in the 14 rural counties and the Three Rurals I am discussing, during the 2020 Census.

The Western Rural region has the highest population of people identifying as AIAN, but their percentage of the total population is not much different from the Central Rural counties, which have the lowest population. It is in the I-80 Corridor counties where the largest percentage of the population self-identifies as AIAN, contributing to the high Diversity Index of the area as discussed in the second “Inside Elko County” article. Note that over 2/3rds of this population lives in Elko County alone—which also contains the highest number of reservations (4) for a single county in the state.

What is striking about the three is the proportion of the population living on reservations—25.3% of the AIAN population in the rurals collectively. In the I-80 Corridor, over a third of this population lives on reservations and over 28.2% in the Central Rurals. Even in the heavily-urbanized Western Rural region over 16% of the AIAN population lives on reservations.

Yet it is important to remember that even with these percentages the majority of the rural indigenous population does not live on reservations or colonies. Many—but not all—live in proximity, which may ease some provisions. But in issues ranging from polling places to utility infrastructure to education, counties increasingly are being called to account for services they should have been providing all along. But one problem—certainly not the only or even most significant—is the lack of clear data about this population.

The education issue currently is particularly important in part because of the relative youth of the AIAN population—which is much higher in the rurals than in urban areas. The chart below summarizes the relative population proportions of AIAN and Under 18 in the major regions I have been discussing (again, based on the 2020 Census):

Overall, the percentage of the AIAN population which is Under 18 is higher in all regions than the total population Under 18. This reflects the continuing trend of growing (and therefore younger) American Indian communities across the nation. But there is considerable variation. For the three urban counties (Clark, Washoe, and Carson City), the difference is just about 2.6%—far less than other groups such as African-Americans or Hispanic/Latinos. This may reflect a tendency of urban areas to draw more working-age Native Americans who may not be establishing as many families in the cities.

The AIAN population in Nevada has a higher percentage of Under 18 than the general population—a situation more pronounced in the Three Rurals than the urban counties.

But in the rurals the difference is pronounced. Some of this is the older population to begin with. But on average the 14 rural counties have AIAN populations with significantly more Under 18s than the general population, with both the Western Rural and Central Rural region having differences above 7%. Even in the relatively young and growing I-80 Corridor, almost 32% of the AIAN population is Under 18—almost 5% higher than the general population and approaching that of the Hispanic/Latino population. The young Native American communities remain closely tied with the reservations.

The more intriguing bit on information for me is the proportion of the Under 18 population which identifies as AIAN. Overall, the AIAN percentage of the Under 18 population is higher than the general population—but only slightly in the case of the three urban counties. The parallel between AIAN percent of the urban population (3.1%) and the urban Under 18 population (3.4%) reflects the more static population in urban areas. In the rurals, however, the AIAN component of the Under 18 population is remarkably consistent at between 8% and 9% and generally 2% higher than the AIAN percent of the overall population. This may just be an oddity of the numbers, but it indicates that rural school districts are regularly dealing with a far larger percentage of their populations coming from tribal communities than is generally acknowledged.

To illustrate this point and conclude the article, I want to do a quick dive into the tribal Under 18 situation in two rural counties where reservations are a significant concern for school boards: Elko County and Mineral County.

Inside Elko County: Te-Moak Communities and the Duck Valley Reservation

As noted above, Elko County has the largest number of reservation communities of any county in Nevada, with four. Three of the reservations are under the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone: the Elko Band Colony, the Wells Band Colony, and the South Fork Reservation (the Battle Mountain Band Colony in neighboring Lander County is also Te-Moak). The fourth is the Duck Valley Reservation straddling the Idaho-Nevada border, which has both Western Shoshone and Northern Paiute populations. Over 77% of the Duck Valley population lives in Nevada.

Overall, the Western Shoshone likely comprise the largest indigenous group in Nevada. The Lander and Nye County reservations are also Western Shoshone, as is the Ely Reservation. The Fort McDermitt, Fallon, and Reno-Sparks Indian Colony membership also includes large numbers of Western Shoshone. The Goshutes are often grouped culturally with the Western Shoshone as well. The lack of a clear means of tracking tribal affiliation as opposed to a broader American Indian or Alaska Native category remains one of the pressing demographic issues for policymakers, tribal or not.

Back to Elko County. These reservations are not spread evenly across the county, but concentrated in the south-central and western portions of the county. And, unsurprisingly, the AIAN population in the county follows this pattern. Below is the map of the Elko Census County Divisions (CCDs) and the percentage of the AIAN population in each:

First, this map is almost a mirror image of the map of the Hispanic/Latino population discussed a few weeks back: the Hispanic/Latino population is significant in the eastern part of the county (particularly in the “Casino CCDs” of Jackpot and West Wendover) while the AIAN population is further west. The relatively high AIAN population in the Montello CCD likely comes from Natives working on the large commercial ranches in the area (there are almost no AIAN children per the 2020 Census).

Of course, in terms of numbers the Elko CCD (the Elko-Spring Creek complex) has the highest numbers of both AIAN and Hispanic/Latino population—although in each case the percentage in this CCD are slightly lower than county percentage as a whole. For the AIAN population, just over 65% of the county’s population lives in the Elko CCD—home of both the Elko Band Colony and the South Fork Reservation. So a large population—but among a larger non-tribal population as well. (For comparison, just over 70% of Elko’s Hispanic/Latino population lives in the Elko CCD).

The Duck Valley AIAN population, however, dominates the northwestern Mountain City CCD, comprising 74.2% of the CCD’s population and 22% of Elko County’s AIAN population. And, more significantly, this population is the youngest tribal population in the county, with just under a third Under 18 (Elko is second at 32.4%). This third represents almost 83% of the Under 18 population in the Mountain City CCD—meaning that almost all growth is coming from Duck Valley.

The relatively young age of Elko’s tribal populations means education is emerging as a point of contention with Elko County and the state governments.

Given the relatively young age of Elko’s tribal populations, education is emerging as a vital point of concern and contention in both communities. Elko County School District’s recent expansion of Title VI grant-seeking is one outcome of this, as is the recent revision of the Parent Advisory Committee to allow Native parents more participation is education decisions. But parent participation is not just coming from expanding options offered by the school district, but also from parents themselves. I mentioned the recent consultants’ report on Elko County’s school buildings in the last Aging Rurals article. Of the seven in-person public meeting held by the consultants, the one in Owyhee was the largest and presented an extensive list of concerns.

The Owyhee Combined School at issue, serving K-12 students, is the only reservation-based school in Elko County. Given that it is almost 100 miles from any other Elko County School, it is also one of the most isolated. The school dates from the 1950s and like many Elko County schools is showing significant signs of aging. But more importantly the school is too small to serve the growing community. The Elko County SChool District consultants claim the school could hold up to 419 students and is currently 72% capacity. Duck Valley officials, however, claim the building was only designed for 120 students, meaning it is at more than double its capacity. Both parties, however, recognize that some significant issues in building infrastructure, technology, and grounds conditions need to be addressed. Unfortunately, the real deciding factor may lay with an issue not included the report: the presence of water contamination which was the topic of a major public hearing earlier this week (read the Las Vegas Review-Journal article here). Schooling issues should not await tragedies to address.

Inside Mineral County: Walker River Reservation

Mineral County is the one county in Nevada where Nevada tribal members represent the largest non-majority population—20.7% at the time of the 2020 Census. Almost the entirety of this population is affiliated with the Walker River Paiute Tribe (the Agai Dicutta Numa, or “Trout Eating People”). While the large Walker River Reservation spans the intersection of three counties—Mineral, Lyon, and Churchill—the majority of the land area and the population lies in Mineral County, centered on Schurz.

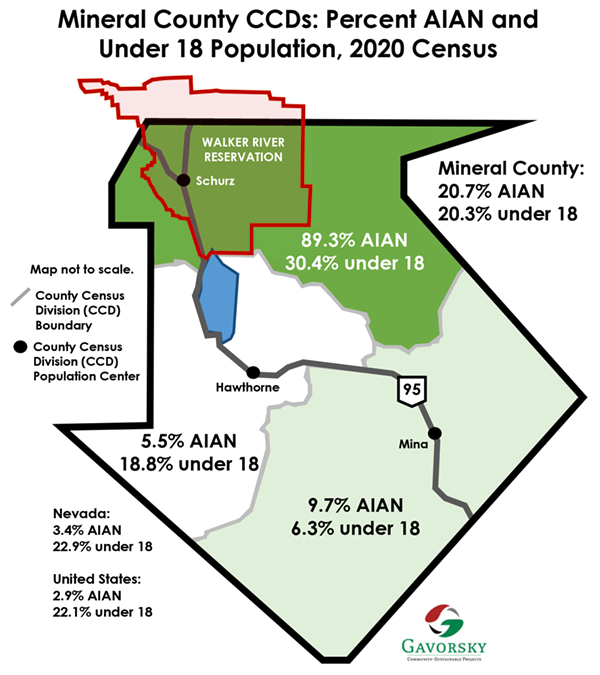

Like Elko County, the Census Bureau has divided Mineral County into Census County Divisions (CCDs), but only three: Mina (just over 200 people), Hawthorne (the county seat). and Walker River (based around the reservation). The map below shows the CCDs of Mineral County, with the percentage AIAN population and the percent of the total population Under 18 in each CCD:

Remember that Mineral County, like the Central Rural region generally, is one of the oldest areas of Nevada. Only a fifth of the population is under 18, 2.6% less than the Nevada percentage of 22.9%. But, as in all rural counties, the population is not spread evenly. Significantly, the Walker River CCD—again, most of the population here is AIAN—has by far the largest percentage of population Under 18 at 30.4%. In reality, it is this population which is bringing up Mineral County’s overall average. Without the AIAN population in Walker River, Mineral County would have the same low Under 18 percentage of the Central Rural region generally (around 17.5%)—the stereotypical Aging Rural county.

There is, of course, a difference between percentages and numbers. The Hawthorne CCD contains 77.6% of Mineral County’s population. In this case, it follows the pattern of population clustering around more developed areas in the rurals. However, the sharp discrepancy in percentages Under 18 means that 29% of Mineral County’s Under 18 population identifies as AIAN. And a quarter of the Under 18 population lives on or in proximity to the Walker River Reservation—far more than the percent which the reservation comprises of the total population.

This means that similar to Duck Valley the Walker River Reservation finds itself with a large school-age population but questionable equity in the process. The Schurz Elementary School, serving grades K-6, has some similar issues with technology grounds condition with the Owyhee Combined School (although it is a much younger school overall) because of the remoteness of the school. However, it is not a combined school—which means that students in junior and senior high grade levels have to attend schools in Hawthorne. This requirement means not only transportation issues, but also the need to bridge the reservation-county government divide on a range of issues from curriculum to equity issues.

Education issues are important for reservations now, but kids grow up. Nevada’s young tribal communities might find themselves playing a bigger role in politics and the economy in the very near future.

But while education issues are a vital concern now, there is also the future dynamic. In short, kids grow up. I mentioned in November’s Deep Red Rurals article on the mid-terms that the tribal vote is starting to play a role in Nevada’s elections, and I believe it increasingly will in the future. It is not a coincidence that two of the largest rural reservation communities—Duck Valley and Walker River—with some of the youngest AIAN populations in Nevada are seeing both increased advocacy from parents but also have been the center of polling lawsuits over the last three election cycles. As these young populations grow up, they will tend to vote. And if they stay in higher percentages in the vicinity of their reservations—increasingly likely for Duck Valley and the Elko Band Colony as Elko’s economy diversifies and also for Walker River where the obvious source for a future workforce for aging Hawthorne is currently growing up in Schurz—tribal communities might find themselves playing increasingly decisive roles in Nevada’s future.

Thank you again for joining me on this dive into the demographics of the Rurals of Nevada. As always, feel free to leave comments or email me any questions.