Rurals of Nevada: Native Communities in Nevada (art. 11)

"The Tribal Nations are not a special interest group or to be considered race based. The Tribal Nations are sovereign governments." - "Nevada's Great Basin Tribes" Legislative Factsheet, 2015.

Indigenous communities have had the most troublesome relationships with the Census and other bureaucratic measures to count them. The complex histories of American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders in American overseas territories are a bit more than can be covered here. But overall the stories are not good.

Indigenous communities in the lower 48 states—American Indians in government parlance but often including Alaska Natives as “AIAN” populations—have had the most fraught experience. The Census Bureau tells its view of this history here. Article I, section 2 of the U.S. Constitution originally excluded “Indians not taxed” from the Census count—the result of the idea that these communities existed as separate from the United States even while sharing the same geographic space. By 1850, however, government agencies were requesting more information on American Indian communities under their jurisdiction, and the “American Indian” race was added to the 1860 Census. The Census Bureau started counting “taxed and untaxed Indians” in 1890, and the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 technically ended the distinction and required all American Indians to be counted. Unfortunately, these communities were heavily undercounted for decades afterward.

When the 2020 Census was being planned, the Census Bureau and indigenous communities worked closely to address both historical issues and more recent problems—namely the Census undercount. While a steady improvement was being made after 1990 in counting all minority populations, the 2010 Census showed a pronounced estimated undercount of 4.9% for American Indians living on reservations and in Alaska Native villages. This was much higher than the estimated 0.9% undercount of the same communities in the 2000 Census and by a wide margin the highest undercount of any minority in 2010 (Black communities were second, with an estimated 2.1% undercount). For comparison, the Census Bureau estimated there was a 0.1% overcount across the nation as a whole. Further complicating the dynamic is that American Indians and Alaska Natives are significantly younger (meaning more children) than most other groups—a double-whammy when the fact that Children Under 5 were the most undercounted age group in 2010 (by over 5.0%).

To correct this issue, the Census Bureau worked closely with groups such as the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), and tribal governments through direct tribal consultations to identify issues and solutions. As this excellent NCAI information page explains, most reservation areas lay within Hard-to-Count (HTC) Census tracts where the combination of remoteness, economic and educational disparities, and histories of distrust combine to lower response rates. Outreach efforts were undertaken by tribal governments to ensure their populations were aware of the importance of an accurate count for the Census and they undertook extensive measures to make sure their populations were counted. I was honored to play a minor role in this process as a Tribal Partnership Specialist, making sure tribal partners had the information they needed and negotiating safe access for enumerators during the pandemic.

The results of the 2020 Census are going to be debated for a long time (for good reasons) and were not as robust as hoped. Overall, post-Census analyses indicated neither an overcount nor an undercount in the national population, as detailed here. But this varied widely. Most minority communities saw a rise in estimated undercounts, including American Indians living on reservations. The White population had a small estimated overcount. Children Under 5 continued to be undercounted. But the most controversial result was that overcount/undercount discrepancies between states, which impacted the reapportionment numbers for the House of Representatives.

For American Indians, however, the reservation estimated undercount has to be balanced with the overall results. The American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) population showed an increase of 85% since 2010, with 9.7 million Americans (2.9% of the U.S. population) identifying as AIAN alone or in some combination. And this is about double the same population in 2000. The number of children was part of this growth, but increased efforts of tribal communities to get their populations counted accurately are more significant. This population was there—they are just now better counted.

In my opinion, Nevada’s 2020 Census count was very accurate despite the problems outlined above. The state was not among those where overcounts or undercounts were significant (i.e., we were not going to gain another House seat). Moreover, Nevada’s Self-Response Rate of 66.6% (the percentage of housing units which voluntarily completed the Census form before an enumerator knocked on the door) was just below the national rate of 67.0% and much better than in the 2010 Census (you can still play with the Census’ nifty Self-Response Rate Map here). The high rate means both that people participated actively (which results in more accurate data) and operational problems of getting enumerators out had a reduced impact. This pattern continued for the reservations as well, despite the pandemic. Nevada had a tribal reservation Self-Response Rate of 51.9%, which while smaller than the general population was the second highest among AIAN communities in the Census Bureau’s seven-state Los Angeles Region (Washington was top at 73.8%). Finally, no reservation in Nevada denied Census enumerators entry to count those who did not self-respond, despite the pandemic. Nevada’s tribal communities worked hard to get their populations counted and the result shows.

With that said, this article series is ultimately concerned with what the results of the Census are saying about Nevada’s tribal communities. That is actually a harder question than efforts to collect a total number might indicate because of how the information is captured. It is necessary to understand how Census data “sees” American Indians and the problems these viewpoints create.

Identity and “Seeing” American Indians

By “identity” above I mean the categories used by the Census Bureau to allow policymakers and researchers to “see” American Indian populations. We thankfully are well past the days when Census personnel ascribed racial and ethnic categories to people. The use of self-identification since 1970 has allowed people to identify themselves—although they are constrained to use categories shaped by policymakers. People know who they are; it is the policymakers at various levels of government who need to be convinced.

By identity, I mean the categories which allow policymakers to “see” populations. People know who they are—it is the policymakers at the various levels who need to be convinced.

Despite numerous concerns (such as expressed in the quote from a Nevada Legislature factsheet from the Nevada Indian Commission at the top of the article), the basic measure for indigenous populations remains the racial category. Based on the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) 1997 federal standards for racial and ethnic data (the Census Bureau is a federal agency, after all), the standards require categorization of ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not) and race in one of six categories—White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or Some Other Race—with the option to select More than One Race (Multiple Races).

The problem comes in how all this information is captured. For Hispanic/Latino ethnic communities, the choice is simple: it is a yes/no box for Hispanic or Not Hispanic. There are increased prompts to collect more information such as ancestry (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, etc.) but the basic results can be read easily.

For the six racial categories, however, the problems multiply—and not just because the question of racial self-identification is a very complex field in itself. The main issue is how this information is reported for policy use. For example, should the primary characteristic or “true” measure be “Race Alone” or the race in some combination? Trying to determine the different levels and their meanings is a mess—just read this Census Brief on the AIAN results of the 2010 Census for an example.

While these issues concern any of the race categories, the impact on American Indian numbers are more pronounced because of the tendency to marry outside the communities in larger numbers. For example, according to 2020 Census data released to date, over 81% of persons selecting “Black or African-American” selected that race alone. For “American Indian or Alaska Native,” the number was 41.5%. And if we break the data down into the same categories as the 2010 Census Brief mentioned above, we get this:

If a policy looks at just AIAN alone, well over half the American Indian population in Nevada would be missed. This is why some advocacy groups were encouraging American Indians to mark “AIAN Alone” on the Census form in 2020. For my purposes, I will just use the total “AIAN Alone and All Combinations" unless specifically noted otherwise.

So far, it seems straight forward despite the issues. This racial classification data can provide a lot of insight, say for school districts estimating Title VI education needs or the Indian Health Service to consider new hospitals (desperately needed in Las Vegas, by the way). But the one group this actually does not help is the tribal governments themselves. This data does not give them tribal affiliation, which is the most important way they “see” their population.

Certainly, the population of a reservation or colony can be searched by geographic area. But not all members of a tribal community live in the geographic area. It is important to remember in this that tribal affiliation has far more consequences than just identity. Key civic markers—tribal enrollment, access to Tribal Employment Rights Office (TERO) services, Indian Health Service (IHS) records, and a range of other ways institutions “see” American Indians—often require frequent contact with tribal governments in ways that other racial groups do not need to do. If I move to another state, I rarely have to be in contact with my past state after the initial move. Such may not be the case with members of tribal communities.

Tribal affiliation statistics are of more use to tribal governments than the racial categories which are more important to non-tribal policymakers.

And note I am using the term “tribal affiliation” rather than “tribal membership.” The distinction is important, because an individual can be an American Indian for some programs and still not be an enrolled member of a tribe. As sovereign states, tribal governments have the authority to set membership requirements. There is quite a bit of discussion about “blood quantums” and other ways membership is set with which non-tribal organizations should not be involved. The Census respects this right and does not ask about enrollment directly. But there are some instances—for example, members of non-federally- or state-recognized communities which wish to become recognized—where Census records showing this population is important (so they can be “seen”). Tribal governments themselves are also increasingly interested in maintaining contact with their off-reservation members.

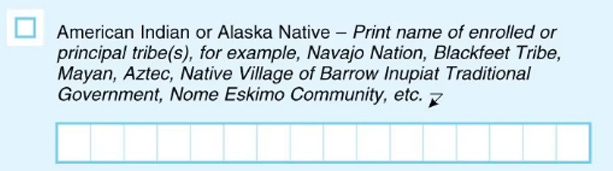

Currently, this is solved in the Census by the “origin” blanks on the Census form. For other races, these might be used to enter ancestry, such as Polish or Nigerian or Brazilian or Vietnamese. But for the 573 federally-recognized and numerous state-recognized tribes, this information can be vital. The problem is how to collect it and report it, which was a major point of contention in the development of the 2020 Census. Here is the final form of the question with examples of possible entries (and the complexity required):

The online form allows up to 200+ characters, and the Census Bureau will report up to six items. So, for instance, someone might list “Walker River Paiute, Mescalero Apache" and both tribes will record an additional person whether or not they are a member.

The question remains will this work—which is unclear because the information has not been published yet. It is coming in the summer of 2023. So we are currently in an odd situation where Nevada’s tribal communities only have about half the information from the Census they need.

This admittedly long digression is necessary because the information needs and reporting standards for American Indian and Alaska Native communities are so unique and do not fully fit into the general usage patterns of a lot of Census data. It is a continued example of the ongoing discussion of how policymakers “see” communities, the problems different views have for policy, and why these conversations have to happen continuously.

Nevada’s Tribal Communities

Since the mid-1960s, the Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada (ITCN) has served as the primary advocacy organization for tribal governments in Nevada. This consortium currently has 28 tribal governments as members—hence the “28 Tribes of Nevada.” These tribes have jurisdiction over more than 1.2 million acres (just under 1.8% of Nevada’s land area). Yet like so much else, the situation for institutional and policy purposes is actually more complex.

The Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada (ITCN) represents the 28 tribes of Nevada which hold just under 1.8% of Nevada’s land area. The policy situation, however, is more complex.

Two of the tribal governments on ITCN are supra-tribal councils (the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California and the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone) each with four reservation/colony councils under them who also sit independently on the council. This is why some sources list only 20 federally-recognized tribes in Nevada. One of the Washoe communities, Woodfords, is entirely in California—but the Washoe Tribe also has a large tract of Off-Reservation Trust land (Washoe Ranches) which they technically control but do not administer as a tribal component. Two other tribal governments, the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe and Fort Mojave Tribe, have reservation land in Nevada but no official resident population on that land. Three other tribes straddle state lines: Duck Valley in Nevada and Idaho, Fort McDermitt in Nevada and Oregon, and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation in Nevada and Utah. Finally, some tribes have a scattered land base composed of non-contiguous holdings which may or may not have small populations on them.

One other issue. I used the term “reservation/colony” because the two have been functionally the same since the mid-1930s with the Indian Re-Organization Act. Historically, colonies date from the early 20th century and were federally-purchased land on the then-outskirts of cities to allow Native Americans to work in those cities without being subject to Nevada state vagrancy laws for, well, being “off the reservation” (California’s rancherias had a similar origin). Curiously, the Census Bureau continues to recognize two separate colony/reservation pairs in its geography: the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Colony and Reservation (Stillwater Reservation) and the Yerington Paiute Colony and Reservation (Campbell Ranch), although these are administered through only two tribal governments (Fallon and Yerington, respectively). Going forward, I intend to use the term “reservation” for any tribal land whatever its origin.

The end result is that if one looks at the Census Bureau’s My Tribal Area app and selects “Nevada,” the Census Bureau “sees” 28 distinct tribal areas in Nevada, one of which is the Washoe Ranches area which has a low indigenous population. But these areas also do not correlate with the 28 Tribes that comprise ITCN nor the actual 24 tribal governments which administer the day-to-day affairs of the resident reservation areas.

The Nevada Indian Commission has this nice map of the tribal areas for reference. It also gives the rough boundaries of the four major cultural groups: the Western Shoshone, Northern Paiute, Washoe, and Southern Paiute.

Finally, the tribal reservation population issue is complicated by questions of other geographies. A number of tribal communities lay across other governmental boundaries. For example, the Duck Valley Shoshone-Paiute Reservation straddles the Nevada-Idaho border, with about half the land area on each side. Approximately 77% of the population is in Nevada and the remainder is in Idaho. For a policy consequence of this, the free college tuition waiver for members of Nevada’s recognized tribes passed by the Nevada State Legislature in 2021 (AB262) is limited by policy to Nevada state residents. That means that Duck Valley tribal members living in Idaho are ineligible, as the Nevada System of Higher Education’s (NSHE) 2021-2022 Report to the legislature admits. The tendency to “parcel out” tribal communities along other jurisdictional lines complicates discussions even when the underlying data is accurate. What the tribal government sees as a whole often has to be presented to outsiders as two parts, with serious repercussions for policy.

Confused? You are not alone. This morass is what happens when different groups “see” populations differently. Issues such as these are major hindrances to creating effective policies and place enormous burdens on indigenous communities trying to work with non-tribal organizations with little recognition of these complexities.

Indigenous Populations in Nevada in 2020

The American Indian population in Nevada in the 2020 Census mirrored some developments seen nationally, but not all. The American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) population, either alone or in any combination, increased about 20.2% from 2010 to 2020. This increase is a bit lower than nationally, but may indicate successful counts earlier. Over 105,000 people self-identified as AIAN in Nevada, 3.4% of the total population.

But when we look at this population more closely, some discrepancies emerge. The AIAN population, like most of Nevada’s population, is predominantly urban. The three urban counties—Clark, Washoe, and Carson City—account for 82.6% of the AIAN population in Nevada. This fact might also contribute to the more accurate count, because “Urban Indian” populations have tended not to show the undercounts of reservation communities.

Nevada’s American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) population is overwhelmingly urban—and has a large percentage of non-Nevada tribes.

Almost 61% lives in Clark County, over 64,000 persons. It was one of the fastest growing areas for AIAN populations in the years leading up to the 2020 Census which attracted media attention (see this AP article, for instance). However, most of this population belongs to tribes outside of Nevada. The two resident reservations in Clark, the Las Vegas Indian Colony and the Moapa Valley Reservation, have a combined population of less than 400 residents, and a slightly larger population living elsewhere in the county. Southwestern groups such as the Navajo and others have been attracted to the economy of the area for decades. Increasingly, various other tribal groups have been attracted to area as well. The 2023 release of the tribal data is going to be necessary to begin to understand this population.

Washoe County is second, with about 18.8% of Nevada’s AIAN population. Non-Nevada tribes comprise the majority of this population as well, but the presence of the Pyramid Lake Reservation, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, and the population of the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe make Nevada tribes far more represented here. Again, tribal data is coming, but I roughly estimate 25% of the AIAN tribes belong to this category. Carson City is similar, although the population here is much smaller (only about 2.9% of Nevada’s AIAN population, less than two rural counties).

The remainder of Nevada’s AIAN population, 17.4%, lives in the 14 rural counties of Nevada. This percentage is larger than the total population living in rural counties. Here, Elko County has the largest population of just over 4,300, although Mineral County has the highest AIAN population percentage at 20.7% (Elko’s percentage is 8.0%). Most of Nevada’s tribal areas are located in these counties, although the reservation population accounts for less than a third of the total AIAN population.

I want to explore this rural AIAN population more in the next article, looking at how the Three Rurals vary and then doing a quick dive into Elko and Mineral Counties.

Thank you again for reading.