Rurals of Nevada - The Aging Rurals, Part 1 (art. 04)

A new "American Gothic" would probably eliminate the farmer's daughter--because rural America is aging, right?

Grant Wood’s classic painting American Gothic has been treated since it was unveiled in 1930 as an object of both admiration for and parody of rural America. The cheaply-paneled house with the ostentatious Gothic window placed amidst the farm setting makes claims to permanence and the grandeur of rural values. The father-and-daughter couple (Wood had clarified the relationship at the time) in the foreground, stoic in their outdated clothing, seem to represent a solidity of experience transferred across generations. A cynic might note that the inclusion of an adult daughter rather than a younger child indicates the unmistakable fact that the future of rural America is hardly auspicious.

The “aging of rural America” is a persistent idea for many. Since 2016, a growing body of journalism has challenged other myths, at least partially embracing diverse rural communities separated by race, ethnic, and economic factors. Some even recognize that some rurals are growing while others shrink. But the idea that rurals inevitably hollow out, that children will leave by the time they reach childbearing age, remains accepted even in otherwise well-balanced discussions of rural myths (see some of the comments from the hosts in this NPR transcript). So one might challenge the white and the farmer and perhaps even the male image of rural America, but no children allowed. The general greying of the United States—both urban and rural—has only solidified a pre-existing image of the aging rurals.

One might challenge the myth of the white and the farmer and even the male components of rural identity, but the aging of rural America is assumed valid.

It was age differences between counties that first raised my interest in the different rurals while I was working as a Partnership Specialist during the 2020 Census. In meeting with local governments and partners in northeastern Nevada to demonstrate the importance of Census data for future policies and funding, I was struck by how often I found myself emphasizing the counting of children for services. Moreover, it surprised many people how young many rural counties in Nevada were—including me after living in Elko for over a decade.

For the next few articles, I want to dive into the question of age in the Three Rurals of Nevada. As always, the goal is to identify some key patterns in the data and look at the implications this might have for policy. Unsurprisingly, these articles are going to draw heavily on Census data. A few caveats are in order at the start.

Brief Comments on Census Data Used

The completion of the 2020 Census (the Decennial, being held every 10 years) is providing a wealth of new data about the American population. The data, however, have not been fully released yet. The main dataset currently available, known as the Public Law 94-171 Summary File, contains only information relevant to the Census’s Constitutional purpose: re-districting of Congressional districts. The file includes data on populations in various geographies as well as racial breakdowns of these populations. Age is included, but in only one measure: population 18 years of age or older. Obviously, this is in accordance with the 26th Amendment’s setting the voting age at 18 and of vital concern to re-districting.

The juicy information—including more detailed age breakdowns and housing data—takes longer to process. According to this press release from the Census Bureau, the age breakdown (along with more detailed ethnic breakdowns, such as Native American tribal identity) is slated for an August 2023 release. Housing data will follow soon after. In the meantime, the P.L. 94-171 is the only data available.

There is one other major Census dataset that contains comparable age data: the American Community Survey, or ACS. Since 2006, the ACS has provided a means to “fill in” data between the decennials as well as collect more detailed information on American life. It does this by starting with the old long-form Census survey tool and then conducting a random sampling of 2% of households in the United States each year (currently about 3.5 million households are sampled annually). This data is then combined with the previous decennial to provide an estimate over a period of time. While 1-year (and formerly 3-year) estimates are available for higher population areas, rural areas often are forced to rely on the 5-year estimates (currently, the 2020 5-Year Estimates, based on 2016-2020 data). More detailed information on the ACS is available here directly from the U.S. Census Bureau.

While excellent data, the ACS has some limitations. First, it is dependent on the baseline decennial used to calculate the estimate. The 2020 ACS, then, is based on 2010 Census data. This renders the dataset somewhat less responsive to unexpected changes such as surges in population growth—which Nevada has experienced since 2010. The sampling protocol is also an issue. In smaller rural communities (and especially lightly populated Native American reservations) the 2% household sample rate means a house in the community might only be sampled every few years. Taken together, these factors suggest the ACS undercounts rural populations, although it varies by how much.

This issue is not entirely the Census Bureau’s fault. Everyone knows that sometimes little humans seemingly pop out of nowhere unexpectedly. And rapid population movements are really difficult to predict—wait until we have to account for the COVID-19 migrations. The accuracy and precision debate is an important one to have about these two datasets.

But not for us at the moment. The purpose of this series is to look at patterns. In my experience, the patterns separating rural Nevada counties are large enough to show up in both datasets. I will, however, be sure to specify which dataset I am using for a particular analysis.

One Universal Measure of Age: Median Age

To look at the question of age in rural areas, there are a number of statistics we may use. But perhaps the most universally applicable for general discussion is the median age. Median age represents the age that divides the population into two equal parts, half below that age and half above it. While lacking nuance for particular data needs (say elementary school staffing or gerontology care), median age can provide a quick comparison between areas to get a sense of their overall conditions.

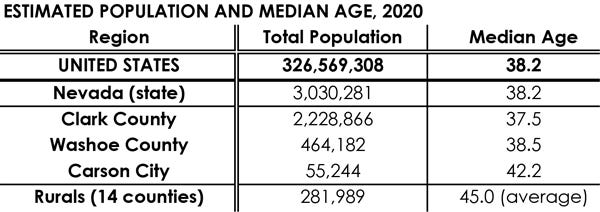

The table below summarizes the median age of the United States, Nevada, the three urban counties, and the 14 rural counties collectively. It is based on the 2020 ACS 5-Year Estimates. Note that I used an average of the median ages of the 14 rural counties, because of limits in the available data about the exact ages in each county which would be required for a precise median age calculation.

Nevada as a whole has a median age exactly that of the nation: 38.2 years. Looking at the four main areas in Nevada, the median age data confirms the generally-held impression of the aging rurals. Clark County (Las Vegas) is slightly younger than the state median, and Washoe is just a tad older—so younger urban areas. But Carson City is much older than the state and the average for 14 rural counties is significantly older—45.0 years, almost 7 years more than the state median. Aging rurals, indeed.

Taken collectively, the 14 rural counties have an average median age of 45 years—almost 7 years older than the state median of 38.2. But when broken down into the Three Rurals, a much more complicated pattern emerges.

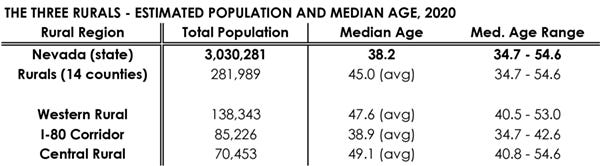

But when the average is calculated for each of my proposed Three Rurals a surprising discrepancy emerges between the regions. I am again using the average of the county’s median ages for each region, but have also included the range of county medians (calculated directly by the Census Bureau). And recall that the Nevada state median age is the same as the national median age.

A clear break exists between the Three Rurals. The Western Rural and Central Rural regions have a markedly older population—nearing a median age of 50 years for the Central Rural. Moreover, although the individual county median age ranges straddle the collective average of 45.0 years, they are all above the Nevada median of 38.2.

But look at the older end of the range. These two regions have the oldest counties in the state. Three of the five counties with median ages above 50 (Esmeralda, Mineral, and Nye) are in the Central Rural area, along with Storey and Douglas in the Western Rural. Four hover around 53 years of age, while Esmeralda is a whopping 54.6 years. In effect, almost half the estimated population of Esmeralda County in 2020 was eligible for senior citizen discounts.

But the more interesting difference is with the I-80 Corridor, with an average very close to the state (and national) median age. The region as a whole is only slightly older than urban Washoe county. And while these five counties straddle the state median age, not one approaches the average collective rural median age of 45.

The I-80 Corridor: A Case for Young Rural Nevada

Let’s look a little bit closer at the situation along the I-80 Corridor because it opens a window to the diversity in rural Nevada. To start, there were 4 counties in 2020 whose median age was less than the state median age. Clark County was one, with a median age of 37.5. The other three were Elko, Humboldt, and Lander Counties—quite a cluster. The fact all three were located in the I-80 Corridor is not a coincidence.

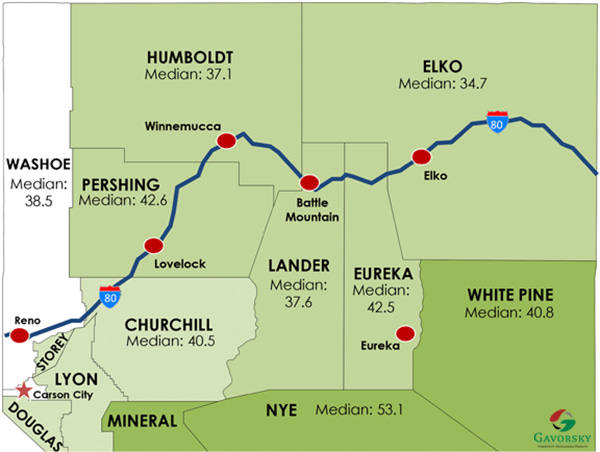

More surprising is the extent of the differences. The map below shows the five-county I-80 Corridor (shaded medium green) with the median ages of each county as well as adjacent counties and median ages.

Note that two of the adjacent counties--Churchill (Western Rural) at 40.5 years and White Pine (Central Rural) at 40.8 years—both have median ages below Eureka and Pershing Counties (42.5 and 42.6, respectively). And both are much younger than Nye (at 53.1 years). Indeed, they are the youngest counties in their respective rural regions but still above the state median age.

But compare the three young counties. Humboldt and Lander Counties bracket Clark County, at 37.1 and 37.6 years, respectively. Elko, however, is very young, with a median age of 34.7—three-and-a-half years younger than the state median age! It is by far the youngest county in Nevada.

So two questions have to be answered: why are the I-80 Corridor counties younger than the other rurals, and why the discrepancy in the median age in Elko County?

The first is easier to answer and likely has already occurred to many readers: the mining industry. Mining is a (relatively) young person’s game. I will be looking at economics more in-depth in future articles, but a few comments are necessary here. Mining is the single largest industry in the I-80 Corridor region, accounting for 48% of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for these five counties in 2020, according to the Nevada Regional Economic Analysis Project (NV-REAP). No other region comes close to this percentage. Three counties—Eureka, Lander, and Pershing—derive well over 50% of their GDP from mining, while Humboldt is at 43.8%. Only Esmeralda (47.8%) and White Pine (49.1%) come close to this importance of mining elsewhere in the state.

Mining is a young person’s game, and mining is the largest industry in GDP terms for the I-80 Corridor. The exception is Elko County—which ironically may explain its youth.

And Elko? Ironically, Elko is the odd county out—which also possibly explains its extremely young population for two reasons. The first is the severe housing crunch in the rurals. Elko is one of the only areas in the I-80 Corridor with the infrastructure (including sufficient water rights) and the construction and capitalization resources to expand housing (even if just barely). While the mines are spread through different counties and record their revenue products in there, many of the workers for Eureka, Lander, and, to a lesser extent, White Pine mines live in Elko and commute. Winnemucca in Humboldt County is serving a similar function for Pershing County mines (with even fewer resources to expand housing). I strongly suspect the reason Pershing and Eureka Counties are not showing the younger populations seen in the other three I-80 Corridor counties lies with the housing crisis.

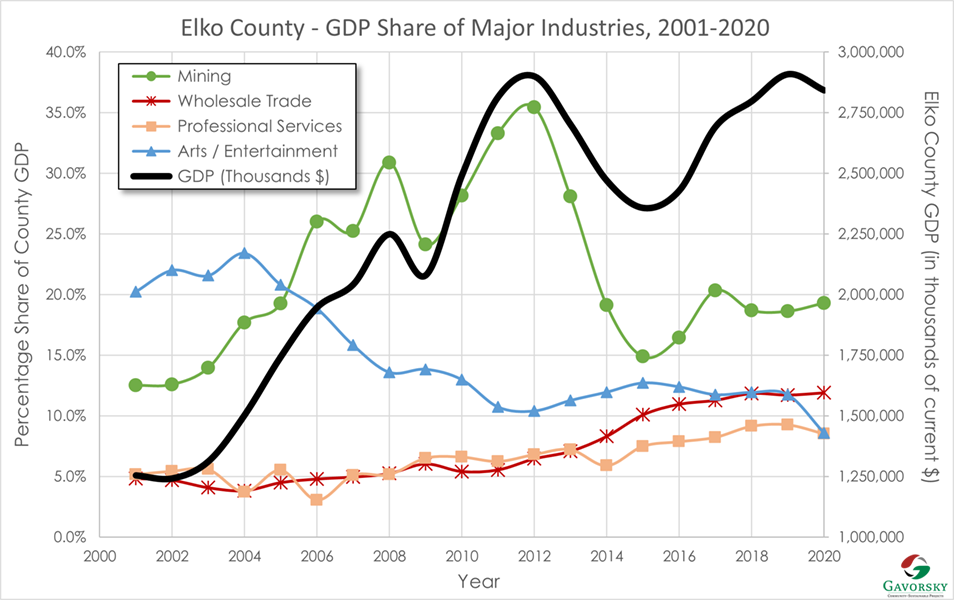

But there is also a second possible reason which in my view has a greater potential for long-term impact: Elko’s economy has been changing over the last 15 years. The graph below is based on NV-REAP data and shows the percentage share of county GDP of some major industries. The GDP itself is the heavy black line (graphed on the right y-axis for comparison).

At the beginning of the current century, Arts/Entertainment/Recreation was the dominant industry in Elko, contributing almost 20% of the GDP. But this industry started a long decline in 2004 and appears set to hover around 12% (the sharp drop in 2020 is the first impact of the pandemic). Agriculture always was a small share of GDP but declined by half over the last twenty years to about 1.4% (too small to include in the chart). Mining itself—that is, the direct revenue from the mines—was important and took off drastically after 2003, well before the Great Recession of 2008. But at its peak mining only contributed about 35% of Elko’s GDP. Currently, it is just over 19% of GDP—about the level it held before the Great Recession.

And up until about 2012, Elko’s GDP growth curve closely paralleled mining’s share of the local economy. Afterward, however, the two graphs begin to diverge, a process accelerating after 2017. What happened? In short, two other industries began to grow: wholesale trade and professional services such as technical, management, and administrative firms. Both areas were about 5% of the GDP in 2001, but have effectively doubled, with wholesale trade by 2018 equal to entertainment. Utilities, construction, manufacturing, and information have seen some growth, but remain minor share contributors to the county GDP, most below agriculture’s share. Despite fluctuations, other industries connected directly to the mining population—retail trade, finance, and educational/healthcare services—retain roughly the same share of GDP in 2020 as they had in 2001 even while more than doubling in amount.

Elko might be in the early stages of a shift towards a more diversified service economy closer to what is found in urban areas. Mining is still central. Certainly, both the wholesale trade and the professional services are largely centered around mining; Elko is servicing the mines located in other counties even more than it is housing the workers for those mines. And since these industries are emerging, they might be attracting younger talent, which helps explain the median age gap compared to other counties. Even the relatively flat growth of GDP share by the other industries indicates a problem not uncommon to economic change: lagging development to support an unexpectedly growing population. If these industries—especially healthcare—expand, they might bring younger professionals into the area in the future as well.

Elko might be in the early stages of a shift to a more diversified service economy more akin to urban areas. But which comes first—the shift in population or the shift in services?

The reason this change may prove significant is that the shift to services brings Elko directly into the debate about the difference between urban and rural. As I discussed in the second article of this series, population concentration is often used as a proxy for the availability of services. For the I-80 Corridor, the services which are establishing themselves in Elko might outlast the current population surge. Even if housing elsewhere expands and the miners (and their families) move to counties closer to the mines, the wholesale trade and professional service industries already establishing themselves in Elko are not likely to relocate. Even medical and retail trade firms which develop might not be easy to displace once established. Remember the USDA’s new FAR Codes incorporate both health care and high-end appliances among the services from which they are tracking distance.

But businesses are not the only headstart Elko has in this change. Elko County’s estimated population of roughly 52,500 (per the 2020 ACS) is 63% of the population of the I-80 Corridor as a whole. In fact, the united population of the city of Elko, where most firms are located, and the adjacent Spring Creek area (unincorporated but effectively a twinned unit with Elko) is over 35,500—greater than the other four I-80 Corridor counties combined. And remember that 50,000 people in an area is a common attribute for being defined as “urban.” The city of Elko might be on track to become an urban area in the next 10-20 years. The “younging” of the population could be an early sign of a huge change.

Are the Rurals of Nevada Aging?

So are the Three Rurals of Nevada aging? The answer for the Western Rural and Central Rural areas is an undoubted yes—but for different reasons which require more exploration in upcoming articles. The I-80 Corridor is a more complicated picture. Certainly, by median age, it is one of the youngest areas of the state in large part because of the need of the mining industry for relatively young workers. But is the growth sustainable and is it likely to be multi-generational?

That gets back to our original question. Are we looking at a temporary youthfulness that might collapse if mining declines and young people move away? Should we continue to hold off on adding the adult daughter back to our new American Gothic painting?

We can’t quite answer that using median age alone. But there is another measure of aging which can help and which allows us to draw on the currently-available 2020 Census data: the population under 18. I intend to dive into that issue next week.

Thank you again for bearing with my statistical meanderings, and please feel free to leave comments and share with friends.

Great stuff Scott. I think the "urbanization" of Elko may be happening faster than you surmise and I would venture that the next bump in population, and a younger one at that, will likely occur in Humboldt Co. with the fish farm and the lithium mine(s)