Rurals of Nevada - Deep Red Rurals (art. 03)

"It means rurals are gonna rural"--Twitter user Werd (@55normalwerd) responding to the early election turnout on 8 November 2022.

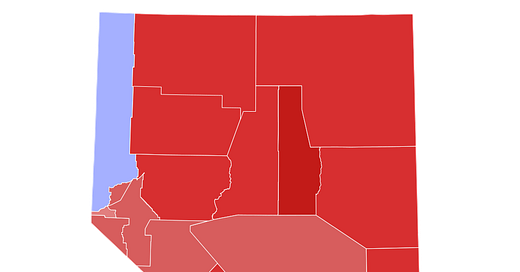

One of the certainties of Nevada politics is the “deep red rurals,” the tendency for the rural counties to vote heavily Republican in every election. The recent 2022 midterm elections proved no exception to this trend, as evidenced by the above map of the gubernatorial race. Most statewide (including the U.S. Senate race) Democrat candidates only won in Clark and Washoe Counties, while Republicans captured almost all the rural counties and Carson City. Incumbent Attorney General Aaron Ford was the only Democrat exception, winning Carson City as well, while Stavros Anthony (Lieutenant-Governor) and Andy Matthews (Controller) were the only statewide Republicans to win Washoe. These results seem to confirm, as one astute observer said, the “rurals are gonna rural.”

Yet they are not “rural-ing” (since it’s apparently a verb now) in the same way. I want to do a quick dive into how this election broke over the Three Rurals I am outlining. This analysis will not be a thorough political analysis, however. I will leave that to those far more knowledgeable about Nevada politics generally. This article from the team at the Nevada Independent provides a good summary of the mainstream thinking on this election. I am more interested in looking at trends underlying the results.

While “rurals are gonna rural” and remain deep red, they are showing differences in voting patterns that might indicate trends that are differentiating the rural counties.

The numbers I am working with are mostly from the Nevada Secretary of State’s Silver State Election website and are as of Monday, 21 November 2022. I still do not have full turnout information at the precinct level, but since the concern is at the county level I can tender this initial analysis. Second, arithmophobes be warned. And please note I am not a supporter of the current idea that registrations-are-destiny in elections, so votes cast is the more significant issue in my view. Finally, I am going to concentrate on the “Big Two” of the Governor and the U.S. Senate races as the clearest examples of differences emerging in the rurals. The close parallels between the two reveal some unity of thinking at both the state and federal policy levels.

Basic Results and the Question of Turnout

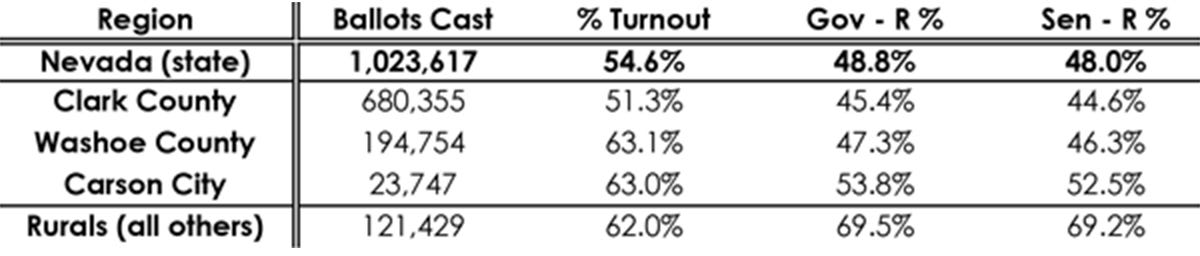

Let’s start with some basics of this election. On the chart below is a simplistic set of results data—total votes, turnout, and Republican vote percentage for the two major races—broken down by the major voting geographies: Clark County, Washoe County, Carson City, and the 14 other rural counties together. As I mentioned in my first article, while Carson City is often considered “rural” (and the tendency to vote Republican is part of the reasoning), I do not consider it to be truly rural. So I have broken it apart separately here.

A few things immediately jump out, even in this simplistic summary. First, there are very few votes within the rural counties. Even with Carson City, they do not come close to Washoe’s vote totals alone. In the 2022 midterms, the 14 rural counties had a collective turnout of 62.0%—over 7% higher than the state average and just below both Washoe and Carson City. Not too shabby but not enough to overcome the numbers advantage of the urban areas. The rural counties’ role is to push the margins of a win rather than directly deliver a victory.

Nevada’s rural counties cannot deliver a candidate victory alone—they can only push the win (or loss) margins for a candidate. But those margins matter.

But those margins matter, due to the overwhelming Republican voting patterns in the rural counties. In the three urban areas, the vote percentages hover around the 45-50% mark for the two major parties. In the rural counties, however, almost 70% of the vote goes Republican. In statewide races which are won by 1-2% margins, the rural vote can mean a significant advantage. Republican candidates in particular are keen to push up the rural turnout—and just as quick to blame the electorate if the expected turnout does not arise.

In this election cycle, the clearest example of the margin argument is the difference between the Governor and Senate races. Republican Joe Lombardo won the Governor race by just over 15,000 votes (about 2%). Senate Republican candidate Adam Laxalt, however, lost his race by just under 8,000 votes (just under 1%). With the exception of Clark (where he ran just behind Lombardo in vote percentage), Laxalt’s share of the vote total was about 3% less across the board—even in the rurals. But his share of the Republican vote hovered within just 1% less than Lombardo. The discrepancy came from increases in Democratic candidate votes. The most likely source of these votes was voters who were consistently less likely to vote for third-party candidates for Senate than they were for Governor. Given that the differences in the rurals between Lombardo’s and Laxalt’s Republican vote margins equaled about 3/10th of a percent indicates vote-splitting was not the issue for Republican voters. It is hard to see how turnout, especially from the rurals, directly impacted this race more than differences in offices or candidates in the voters’ eyes.

There was, however, one significant issue with voter turnout in 2022 which impacted the election. In January 2020, Nevada implemented automatic voter registration through the DMV (motor voter). So anyone moving into the state, coming of age, or renewing a driver’s license would automatically be registered to vote or have voter information updated (unless they explicitly decided to opt-out). This change was praised for the large number of new voters registered—indeed, over 310,000 between the 2018 and 2022 elections.

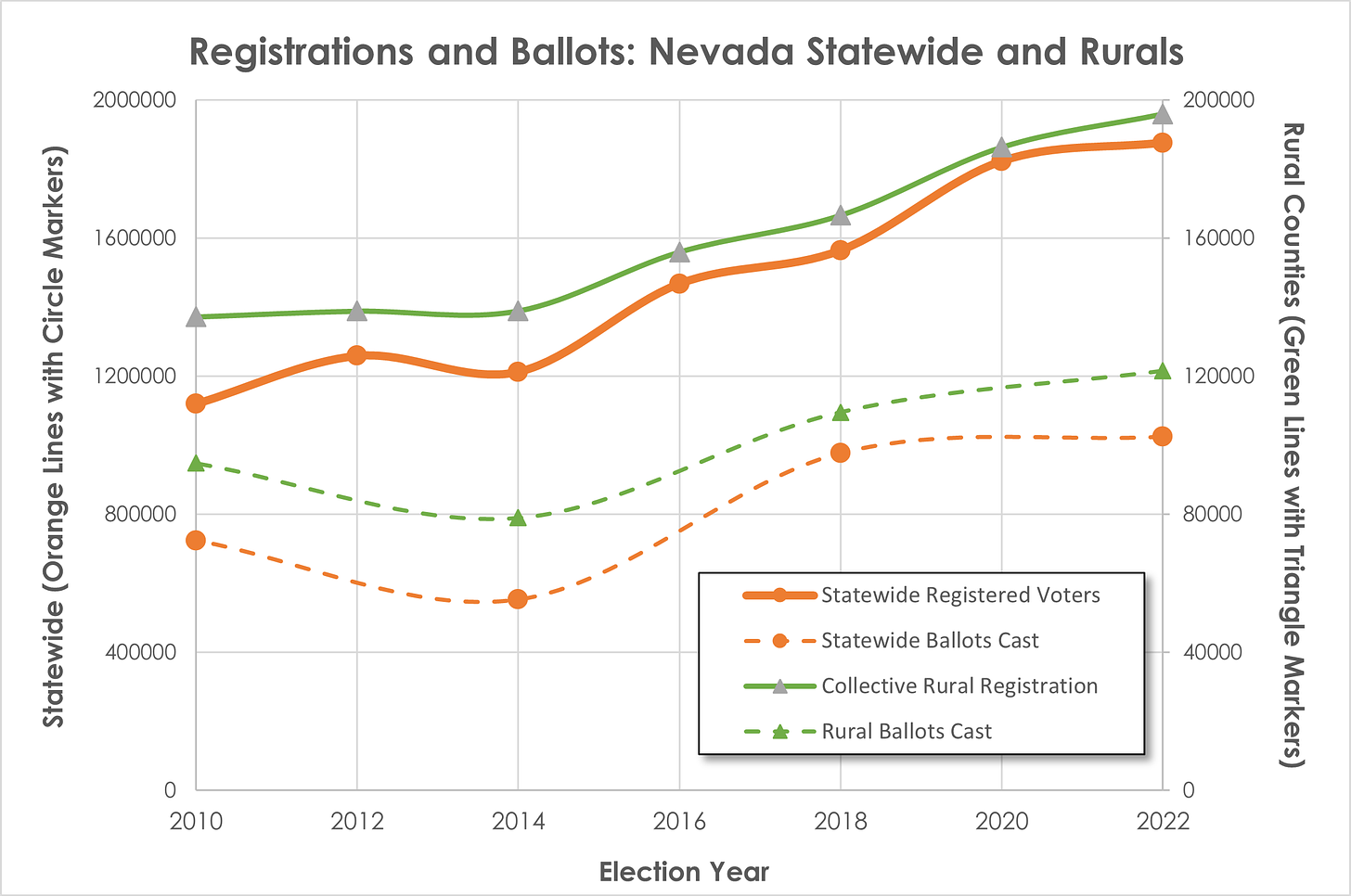

But did this result in new voting populations? The chart below tracks these changes. The statewide changes in registrations across all elections since 2010 and the ballots cast in midterm elections are presented in orange against the left X-axis. The same information for the 14 rural counties is in green, although presented in a different scale on the right X-axis to emphasize the trends.

Two important points are evident in this graph. First, the implementation of automatic voter registration did cause a bump in registered voters—but less change in the number of ballots cast statewide in the 2018 and 2022 midterms. With more than 310,000 voters registered since 2018, less than 48,000 additional ballots were cast in the 2022 election—under 16% of the voter registration. Basically, voting turnout declined while the number of votes increased. Merely adding registrations is not sufficient to generate votes, but provides a wonderful excuse for blaming the voters for candidates who do not win.

As a parallel, the same thing happened with the 26th Amendment lowering the voting age from 21 to 18 in 1971 (which, by the way, Nevada has yet to ratify). Voter turnout dropped over 5% between the 1968 and 1972 presidential elections and has remained below earlier turnout averages since, even with the increased turnout of 2020. These low turnouts are often taken as evidence contemporary Americans are not “civic-minded” compared to other countries. But Americans did not lose interest in elections; we merely added numbers of young people who tended not to vote in the first place. A similar argument could be made for the 2022 midterms.

Adding registrations is not sufficient to generate votes, but provides a wonderful excuse for blaming the voters for candidates who do not win.

Second, note that the rural counties have much flatter curves than Nevada as a whole. This difference is undoubtedly related to differences in growth rates. And, indeed, the registrations added in the 14 rural counties equaled about 9.4% of all registrations in Nevada, about equal to the rurals’ share of the state population.

But note that the rurals’ curves continue to rise after the 2020 election, indicating an increase in both registrations and ballots cast. Indeed, these changes are striking. Just over 29,000 new voters were added after 2018, but there were almost 12,000 more ballots cast in 2022. This equals almost 41% of the new registrations. Somehow, the rurals are motivating more people to vote even as new registrations are suppressing the vote turnout figures.

The Three Rurals: Solidly Republican, but Varied

So, the “deep red rurals” hypothesis is rooted in actual voting practices and the 2022 midterms were no exception. But was it consistent across all Three Rurals? The answer, surprisingly, is no. When the rurals votes from the three areas are considered using the same categories as above—well, that’s where it gets interesting.

First, there are two intriguing sets of alignments among the rurals. The I-80 Corridor and the Central Rural areas had almost the same number of ballots cast, each about 45% of the Western Rural region. And remember from the last article these two areas are also linked by parallels in population density. One would think that the I-80 Corridor and Central Rural counties would vote in parallel. Yet note that it is the Western and Central Rurals have very similar turnout and Republican vote percentages. From these statistics, they are more alike than the I-80 Corridor counties. So what is driving these differences?

We can start with the Western Rural region. The high-population counties, Douglas and Lyon, were watched closely because they have traditionally delivered huge margins for Republican candidates, which they continue to do. The Western Rural counties have also seen the largest increase in registrations, over half of the rural total. They also had an increase in ballots equal to almost 41% of new registrations. These two factors indicate that the new registrants are more likely to vote (probably because they are older) than those in more urban areas of the state.

There is one important difference amongst the Western Rural counties, however. Third-party candidates (including the perennial also-ran “None of the Above”) captured over 5% of the vote in the Governor race in Churchill, Lyon, and Storey Counties, and about 1% less in the Senate races. This is par with the averages in both the I-80 Corridor and Central Rural counties. In Douglas County, however, the third-party share was less than 4%—putting it about equal to Washoe County. The Republican percent margins were also lower in Douglas County, 34% for both races as compared to 42-48% in the rest of the Western Rural counties. Douglas’ population appears to be trending to traditional two-party votes and less Republican as well.

While the rural counties generally are motiving new registrants to vote at higher levels than the state generally, automatic voter registration is driving down turnout numbers—particularly as the non-partisan registrations increase in the I-80 Corridor.

It is clear that the I-80 Corridor (Elko, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing Counties) was the most Republican area of the state, by a large margin, even though turnout was significantly lower—almost 4% lower than that of the rurals collectively. Why the lower turnout? Again, it has to do with the changes in the registration issue. The I-80 Corridor counties had over a quarter of the new rural registrants since 2018—but increases in ballots cast equal to less than 23% of the new registration. The reason, I believe, is that most of the population growth is coming from younger people moving into the region—who tend to vote in lesser numbers. I will be talking about the age demographics in the next few articles, so just bear with me for now.

The low turnout, then, is not disengaged existing voters, but uninterested new voters. Looking at the party turnout in Elko County, the most populous by far of the counties along the I-80 Corridor, provides further evidence. [Disclosure—I was monitoring the Elko County turnout on behalf of the Elko County Republican Party] Almost 69% of registered Republicans cast ballots and 62% of Democrats. Those are excellent numbers any party would be happy to see in a mid-term election. For those registered as non-partisan—the default for new registrants not interested in voting—the anemic turnout was 36%. Even if the Republicans had driven party turnout to 90%—a wildly unrealistic number even considering the 2020 Presidential Election turnout—Elko County would have only added around 3,000 votes total, and it is hard to see the rest of the I-80 Corridor adding much more (Eureka County indeed delivered almost a 90% Republican vote margin)

In short, the I-80 Corridor continues to provide a significant margin advantage to Republicans—among registered Republican voters. Where the low turnout is impacting calculations is the huge number of third-party voters who are not voting at all. Future Republican campaigns will need to develop new techniques to reach these voters if they want to increase the rural margins broadly.

Central Rural: Why the Split in Voting?

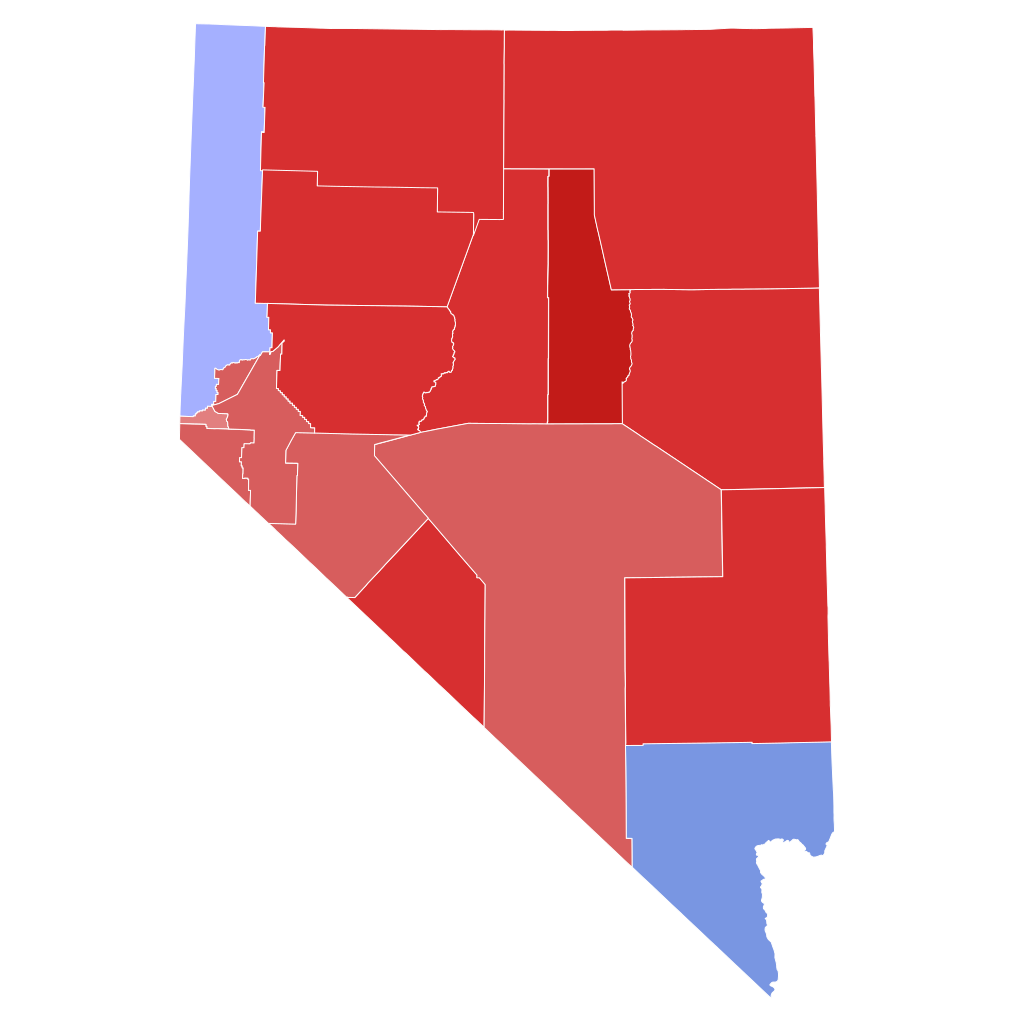

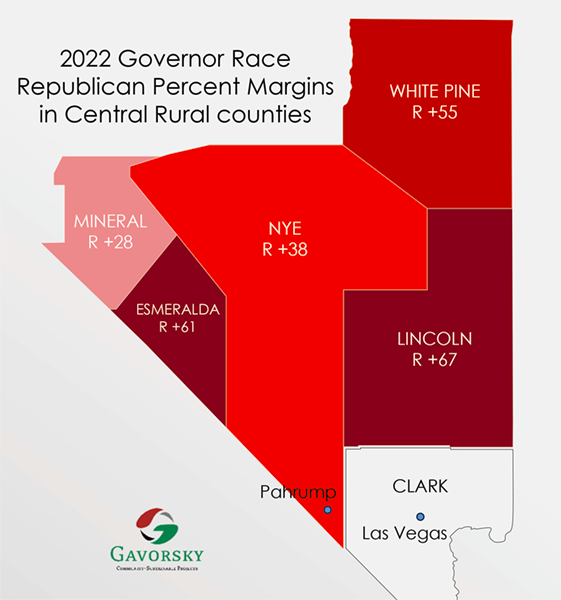

And that leaves us with the most puzzling of the rural regions in the 2022 Midterms—the Central Rural counties. It was the only region that showed considerable variation with the region. The map below shows the region and the Republican percent margins in each county.

Three of the counties (Esmeralda, Lincoln, and White Pine) mirrored the I-80 Corridor “deep red” model with Republican margins of more than 50%. Yet Mineral County produced by far the lowest Republican margin in the rurals—28%. And Nye County came close to Douglas with a margin in the 30s. Why the Western Rural region did not vote the same as the I-80 Corridor comes down to these two counties.

Sparsely-populated Nye County’s voting pattern is the result of the growth of Pahrump in the southern part of the county. About an hour from Las Vegas, Pahrump has emerged as an exurb of that city, both for retirees and those seeking a more “rural” life. As of the 2020 Census, it held almost 87% of Nye County’s population. Nevada’s largest county has one of the most extreme population imbalances within the state.

And by virtue of its size, Pahrump is weighing heavily on Central Rural’s voting patterns. Of the region’s 6,222 registration increase from 2018 to 2022, over 5,100 of those were in Nye (and mostly Pahrump)—an astounding 82.4%. It is the only area in the region gaining significant population. And given that the Central Rural region saw an increase in ballots cast of almost 3,900—equal to 62% of new registrants—it seems that Pahrump’s population growth is becoming less Republican and more likely to vote (similar to Douglas County).

Mineral County has a different pattern emerging, but one which might have broader implications for Nevada elections generally. While the county is one of the oldest in Nevada and not growing strongly in population, it has one unique difference. It is the one county in Nevada where Native Americans are a significant portion of the population—over 20% as of the 2020 Census (more exact numbers will be available next year). The Walker River Paiute Tribe has been engaged in extensive voter outreach efforts spearheaded by Democrat-aligned groups since 2016, and I suspect that the relatively poor showing of Republicans in Mineral County is the direct result of these efforts. I am still waiting on final precinct-level data for the county, so will definitely have to re-visit this issue.

Recent increases in Native American voting turnout can be an emerging disrupter of rural voting patterns—one of which has received very little analytical attention.

The Native American turnout has the potential to be a major disrupter of rural vote calculations, especially if registrations among reservation populations rise. In Elko County, Precinct 29 (which represents the Nevada portion of the Duck Valley Shoshone-Paiute Reservation) has seen increased voter turnout in the last two elections, although registrations remain low. And it is possible that the lower Republican performance in Douglas County might in part reflect increased Washoe voter turnout (Nye County’s Native population is much lower). Finally, it is possible that high turnout among the Pyramid Lake, Summit Lake, and Reno-Sparks Indian Colony members in Washoe added a few thousand votes to the Democrat total in the Senate race. This is an issue that has received very little attention in the 2022 Midterms post-game analyses yet.

Do the “Deep Red Rurals” Still Exist?

So, are the rurals as truly “deep red” as the popular imagination holds? Yes—for now and likely in the near future. But this situation is changing and elections are not going to follow the same pattern going forward. The shrinking percentage of the population in the rurals is going to make it more difficult to find enough votes to decisively shift elections. Limiting efforts to bumping up only existing party registrants will make this effort even more difficult.

Future elections in Nevada can not depend on running up the party turnout in the “deep red” rurals. Candidates will need to win third-party voters, non-partisans, and changing demographic groups by addressing their concerns directly.

Individually, the differences between the Three Rurals will force campaigns to take different approaches. The older “single rural Nevada” messaging is only going to become less useful as the counties diverge. The growing party-line split in Douglas County and Pahrump more akin to urban areas means approaches similar to those used in Reno or Las Vegas might be more appropriate. The large, young non-partisan rural population in the I-80 Corridor will have to be wooed into politics and then into voting for a particular party. Finally, the Native American population will increasingly play a role in political calculations.

Finally, note that the danger of the changing rurals can impact both parties, which is why they cannot simply be ignored. The different vote totals in the Governor and Senate races indicate this. The Republican margins can still be dangerous for Democrat statewide candidates, particularly those who tended to ignore (or even visit) the rural counties like the current Governor. I do not think it is a coincidence that Senators Cortez-Masto and Rosen (who is up for election in 2024) have been more active in the rurals than their predecessors. Republicans, for their part, cannot just sit back and depend on massive rural turnout to substitute for poor margins in urban areas. They will have to begin appealing to both urban and rural voters on the issues. Weird idea, huh?

That about wraps up my initial take on the 2022 Midterm Elections. Please leave me a comment; I am interested in hearing the other views on this election.

Next week, I want to start analyzing an issue that actually started my interest in the Three Rurals: the concept of aging rural America. Until then, enjoy your holiday weekend and be safe if traveling.

Mineral County was also the only rural county to approve Ballot Question 3; most likely due to support from Native American voters.

Great analysis!