Votes, Voters, and Populations, Part 1: Does Anyone Have an Accurate Count for Rural Nevada? (art. 17)

Wading back into the political controversies as the 2024 Election hysteria gets underway.

I generally attempt to avoid politics directly in these articles, preferring to concentrate on policies. It is a bit of a hopeless task from the beginning, since both politics and policies derive from the same Ancient Greek root, πολιτεία (politeia), the citizen community of the polis and its government. The Greeks tended not to see a separation between the two. I would argue that it is only the modern 20th- and 21st-century technocratic imagination that has marked the two as separate, that something like policies for the community divorced from the politics of the community exists. Plato’s guardians-cum-philosopher kings, indeed.

Sigh.

What has caused me to consider this issue is the start of the 2024 Election season and another round of arguments over voting. Here in Elko County, we have been debating election reforms such as attempting to move from machine-counted to paper ballots (for the record, I do not support the paper ballots—I do not think the machines are the issue here in Elko). But in the most recent Elko County Commission meeting on the subject at the end of March, the discussion turned to voter registration and reporting concerns, particularly the current lawsuit filed by the Republican National Committee (RNC) against the State of Nevada for failure to maintain accurate voter registration.

Both the Nevada Current and the Nevada Independent are covering the lawsuit and the Nevada Secretary of State’s office has been very vocal in calling it a nuisance. While I think there are some significant issues with Nevada’s voter registration system and how its data is presented to the public (more incompetence than corruption, in my opinion), I think the RNC is looking in the wrong place. They will lose this lawsuit—in large part because of very shoddy statistical arguments.

What intrigues me about the RNC lawsuit are the demographic questions at its heart.

But what intrigues me about the lawsuit are the demographic questions at the heart of it. The basic argument is that there is a population of eligible voters reported by the U.S. Census Bureau in any given county. And then there is some “standard” level of voter registration among that eligible population—although how one defines this escapes me (the lawsuit seems to assume that all counties in Nevada should have roughly the same number of registered voters as the state average). If a particular county somehow differs from this standard level, the deviation serves as de facto evidence of failure to maintain voter rolls.

There are a lot of assumptions here to unpack, so prepare for another multi-part look.

To start, there is the question of establishing the eligible population—which surprisingly is a key part of the controversy in these disputes because there is no acceptable basis. The problem lies in what dataset is used and how accurate it might be—and the more disturbing fact there is no consensus on this issue.

Four U.S. Census Datasets

When I looked at the myth of the “Dying Rurals” and how that does not apply to parts of rural Nevada, I started with a brief discussion of the two basic Census Bureau datasets used for population numbers (read the discussion here). These are the Decennial Census, required every 10 years by the U.S. Constitution, and the American Community Survey (ACS), a yearly sampling of approximately 2% of American households (roughly 3.5 million) which since 2006 has provided the main dataset for intra-decennial population data.

Both present real problems with getting accurate numbers. The Decennial Census is still one of the best and most highly regarded population counts in the world—but only once every 10 years. The ACS is even more problematic since it is a population estimate based on a sampling of the population, albeit a very good one. As I have discussed, however, the sampling technique tends to lead to a lag in population counts in rural areas which are forced to wait on 5-Year estimates for their population counts. States and larger urban areas can use the 1-Year estimates because they will have enough sampled population yearly to meet the accuracy requirements.

The RNC lawsuit relies on two different datasets, the unique Consumer Population Survey (CPS) and the Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP), based on the ACS.

However, the RNC lawsuit relies on two other datasets. The first is the Consumer Population Survey, or CPS. The CPS is a monthly sampling survey that is conducted on behalf of another federal agency, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Originating with the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration (WPA) as a means of tracking employment across the country, the CPS was taken over by the Census Bureau in 1942. Even today, most people know the CPS as one of the sources of unemployment statistics.

The CPS, like the ACS, is a household interview survey. Each month, about 60,000 households are contacted with questions about the employment status of all members of the household. It is not a new set of households each month; there is a pattern of overlapping periods where the survey is re-administered to selected households. The U.S. Census Bureau summary of the methodology can be found here. While the survey is currently undergoing a modernization project (which all surveys should do on occasion), the more than 75 years of data is an important policy resource.

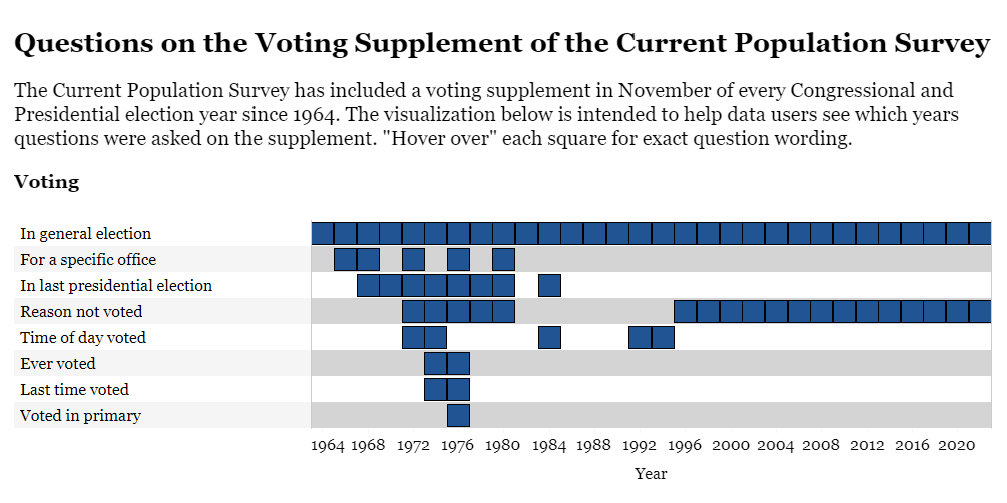

So how did it become the basis of a political lawsuit? Since 1964, it has provided an easy survey to add a few questions about voting practices (known as the Voting Supplement) to the November survey every two years for federal elections. It therefore provides in theory a good snapshot of the voting during elections and is widely used to track participation levels. The timing of this adoption was not a coincidence; the CPS provides much of the data for Voting Rights Act adherence. Like the economic data, this is based on household interviews where a single person answers questions for all members of the household.

The second dataset referred to in the RNC lawsuit is the Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP). This dataset is derived from the ACS 5-Year Estimates, but only includes citizens over the age of 18—that is, those eligible to vote. The CVAP also specifically breaks the data down readily between not only state, county, and other geographies, but also federal and state legislative districts to make those areas easier to find. Since fully implemented in 2010, this data set has increasingly been used for voting rights tracking. Yet since it is derived from the ACS data, it has the same problem with representativeness. For urban areas, it is likely very good. For rural or very small minority populations, caveat usor.

All of these datasets present significant problems, especially when used for the fine-scale effort at determining eligible voters. I want to delve into the voting specifics in the next article. But to see the potential issues, we can look at the various datasets more broadly.

Some Numbers for Nevada

I have mentioned numerous times that the U.S. Census Bureau highly recommends using percentage comparisons of most of its datasets rather than the actual numbers. The problem is for voting calculations, individual counts matter—especially when races are increasingly being decided by 20,000 votes or less.

Of the four datasets we are discussing—the Decennial Census, the American Community Survey and its derivative the Citizen Voting Age Population, and the Consumer Population Survey—only the Decennial Census represents a direct population count. But it only takes place once every 10 years—meaning the counts tend to not capture population changes between the decennials.

The ACS—which remember is also the base dataset for the CVAP—is an estimate, based on a fairly robust yearly sampling of about 3.5 million households. While the 1-Year estimates can be fairly accurate areas with populations over 100,000 people, less populated geographies have to depend on the 5-Year estimates, introducing significant lag in numbers.

Let’s start with a basic measure that seems non-controversial: the total Nevada population. For the moment, I am talking about all people, regardless of age or citizenship status. So let’s start with the three basic datasets that cover this population at the state level: the 2020 Census, and the ACS 5-Year and 1-Year estimates.

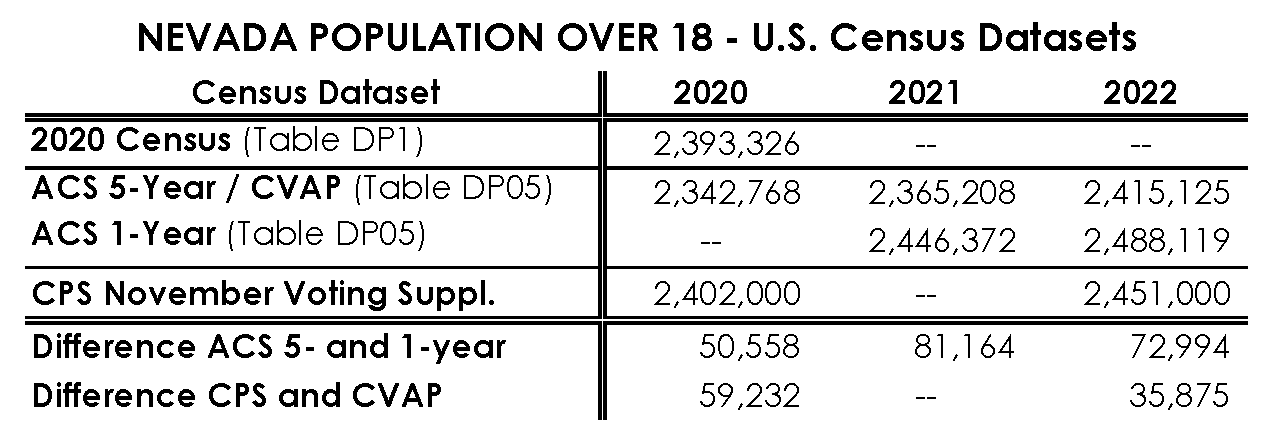

The table below summarizes the three datasets from 2020, 2021, and 2022. Note that the ACS 1-Year is not available for 2020; the Decennial Census takes its place. So the ACS 5-Year represents the only consistent dataset across the period—which provides a baseline to do a rough test of comparison. For simplicity, I refer to the ACS 5-Year estimate by the year in which it is released, although the data was collected over the previous 5 years. So the 2022 ACS 5-Year collected data from 2018 through 2022. I have also included the specific Census data tables used for those playing the home version of the game using data.census.gov.

If nothing else, this table demonstrates that the ACS 5-Year estimates consistently produce smaller population totals than either the Decennial Census or the ACS 1-Year. The differences between the datasets are fairly consistent, averaging between 2.3% and 2.8% (from 73,000 to 85,000 people). This discrepancy makes sense: the 1-Year estimates can capture population fluctuations much easier than the 5-Year estimates. Let me note again that the ACS 5-Year estimates are not averages, but all the survey responses for the previous 5-year period are compiled into a single estimate. But with either method, the ACS 5-Year will not capture short-term fluctuations; there will always be a lag. Yet given the relatively small variation and its consistency, solid demographic work overall.

As the old saying goes, close enough for government work.

The American Community Survey data might be close enough for government work—but not for voting.

Except for voting. The difference might not seem much until one puts it into perspective. Given that Nevada’s four Congressional districts each represented just over 777,000 people after the 2020 Census re-districting (the U.S. Census Bureau has a summary of representation levels here), the roughly 75,000-person difference therefore equals approximately 1/10th of a U.S. Representative.

The more profound issue is when this data is used in increasingly close political contests. Remember that the 2020 Presidential Election in Nevada was decided by just over 33,500 votes (per the Nevada Secretary of State)—about half of the consistent discrepancy in the various Census datasets.

By now, some readers are likely arguing there is a fundamental issue with my data—namely, that one has to be 18 years old and a citizen to vote. Fair point. We can also then begin looking at the CPS data from the Voting Supplement as well.

The table below summarizes the 18-and-older estimates (or count from the 2020 Decennial) from 2020, 2021, and 2022, based on the same tables as above. Recall that the CVAP dataset is based on the ACS 5-Year estimates, so they are combined. I also used the 2020 Census data as a replacement for the ACS 1-Year estimates. The CPS Voting Supplement questions are only added every two years, so I am just using the two from the period covered by the table—the November 2020 Voting Supplement Table 4a and the November 2022 Voting Supplement Table 4a. Note that given the relatively small sample included in the CPS, the data is reported in thousands (so the November 2020 Nevada Over-18 population is reported as 2,402 thousands in the CPS).

Again, the ACS 5-Year estimates produce consistently lower numbers than the ACS 1-Year and the CPS November Voting Supplement. Generally, however, the difference is slightly smaller than that of the entire population. I did make one error, however. Note that for 2020 I used the 2020 Census data in place of the ACS 1-Year estimate. Given the improved accuracy of the Decennial count as opposed to the ACS 1-Year estimate, the 2020 difference is probably in reality larger, closer to the difference in the first table on total population.

What is interesting is that there is a smaller difference between the CPS estimate and the other Census datasets. For November 2022, the CPS estimate came in almost exactly between the two ACS yearly datasets.

However, there is still one further factor in using the Census datasets for voting: not all those 18 and older are eligible to vote. Most importantly, only citizens are legally able to vote (ignoring a few experiments in some municipalities). Despite the misconception created by the lawsuit over the citizenship question on the 2020 Census, the ACS and the CPS both ask about the citizenship status of members of the household being sampled. The table below represents gives the results, again for 2020, 2021, and 2022.

For the third time in a row, the ACS 5-Year gives the lowest estimates. The CPS is again in November 2022 between the two ACS estimates—although this time much closer to the ACS 1-Year than the ACS 5-Year. I suspect this is a result of the ACS 1-year and the CPS ‘capturing’ the influx into Nevada following the pandemic lockdowns. Again, the ACS 5-Year lags a bit because of the methodology, attenuating these migrations.

But what is interesting about this table is that the differences between the surveys are so much higher than the previous tables—particularly in the case of the CPS. The CPS has had a reputation for producing higher turnout numbers during elections from almost the beginning (see, for instance, the boxed text on page 2 of the “Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2020” paper). The likely explanations for the higher turnout numbers are poor memory of the household reporter (they might not be sure if others eligible in the household voted) or poor question design.

But confusion about citizenship seems rather counter-intuitive. Since those citizens over 18 are much smaller than the population 18 and older or the total population. Moreover, while it might be easy for someone in a household to be unclear as to when and how someone else voted, it seems odd they would not know the citizenship status.

I have no explanation for this discrepancy—but it represents a significant lacuna in being able to discuss eligible voting populations.

Remember the Rurals of Nevada?

To paraphrase Arlo Guthrie, this is an article series about the Rurals of Nevada. So let’s turn our attention to the Rurals of Nevada.

As I mentioned, the CPS does not cover down to the county level since the sampling pool is so small. Incidentally, this is one of major flaws of the RNC lawsuit. However we can derive some useful data from the ACS 5-Year estimates about the number of citizens over 18, which should correlate roughly to the possible maximum number of possible voters. It might also say something about voting overall in Nevada.

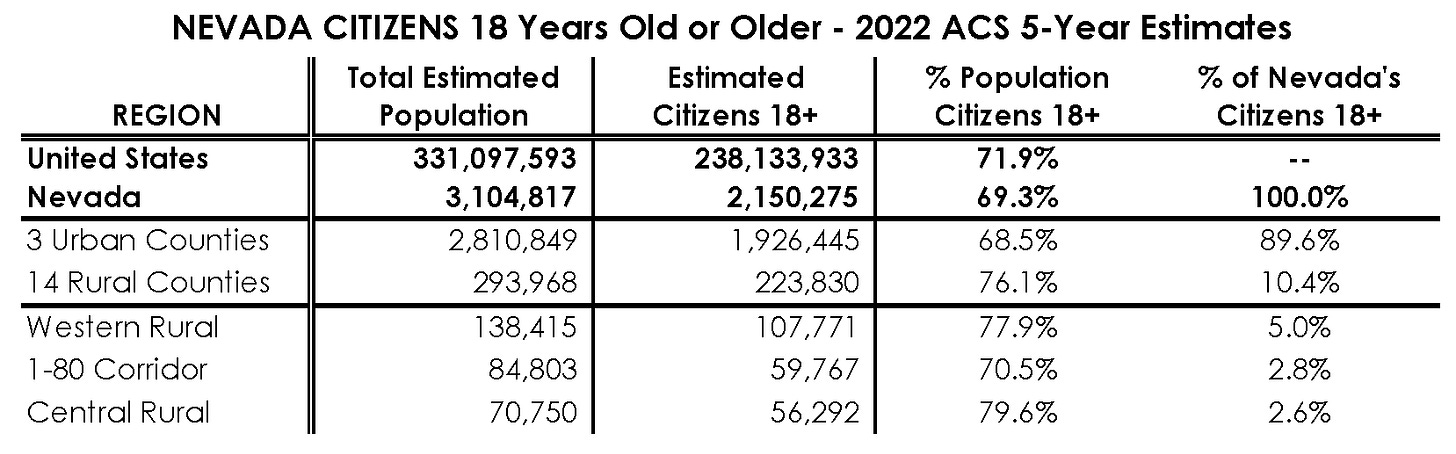

For this, I am going to look at the 2022 ACS 5-Year Estimates since the question here is a snapshot difference between regions. I am also going to go back to using percentages rather than raw numbers because I believe it will be easier to show the differences I am seeing. The table provides two key percentages: each region’s percent of the total population who are citizens 18 years old or older and the percent of Nevada’s Citizens 18 or older population within each region.

One key point before we get into the discussion: the “Citizens 18 and Older” measure is NOT necessarily a measure of the citizen/non-citizen population in these regions. It also includes the portion of the population under 18, whether they are citizens are not. So regions are that generally older—such as the five-county Central Rural region (Mineral, Esmeralda, Nye, Lincoln, and White Pine counties)—are likely to have larger percentages of citizens over 18 because they have more people over 18. Younger areas will have fewer citizens over 18 because they have more people under 18.

With that caveat, there are a few interesting dynamics evident in this table. First, Nevada has a slightly lower percentage of citizens aged 18 or older (about 2.5%). Since as I have note elsewhere that Nevada has only a slightly higher Under 18 year old percentage than the national average, so I suspect a large part of this discrepancy reflects a rough count of non-citizens. But that is another discussion.

Second, note that the 14 rural counties (recall that I classify Carson City as an urban area along with Clark and Washoe counties) represent 10.4% of the state’s citizens over 18. This exceeds the 14 rural counties’ share of the total population by almost a full percentage point. In other words, the rural counties have a larger potential share of their population eligible to vote.

The 14 rural counties have a higher percentage of their populations who are Citizens over 18, and therefore eligible to be registered as voters.

This potential is readily apparent by the third intriguing result. Citizens over 18 years old represent over 76% of the population of the 14 rural counties. That is 7.6% higher than the 3 urban counties—a significant difference. I believe the difference lies with the much older population in the rural counties.

However, as a long-time reader might guess, the three rural regions are not equal. The two older regions, the Western Rural (Churchill, Douglas, Lyon, and Storey counties) and the Central Rural discussed above have 77.9% and 79.6% of their population who are citizens over the age of 18, respectively. Again, this is a consequence of the aging population in these counties.

The outlier, as in so many other areas, are the I-80 Corridor counties (Elko, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing). The percentage of the population who are citizens over 18 is over 7.5% lower than in the other two rural regions. The Over 18 citizen percentage here is just above the 3 urban counties. My interpretation is that this is a reflection of the very young age of these counties and their larger populations under 18. It might also reflect some demographic changes from the recent influx into this area.

Taken together, this table points to one important factor involved in the RNC lawsuit: rural counties are likely to have a larger percentage of their populations eligible to vote. And since there is a long-established correlation between age and the tendency both to be registered and to vote, it is not surprising that several rural counties have higher percentages of registered voters. The idea that each county in the state should have roughly equal voter registration is fundamentally flawed.

Conclusion: What We Know is Not Much

Much of the Nevada Secretary of State’s pushback against the RNC’ lawsuit is premised on the fact that the arguments are based on mixing and matching the various Census datasets that do not align—”comparing apples to orangutans,” in the rather unprofessional phrasing in the state’s second response letter of 18 January 2024.

They have a point. The various Census datasets we have looked at here simply do not have the accuracy to establish the ‘correct’ number of eligible voters. This issue has been adjudicated in previous failure-to-maintain-voting-records lawsuits. The most significant, referenced by the Nevada Secretary of State’s letters, is Bellito v. Snipes, 935 F.3d 1192 (11th Cir. 2019), dealing with an almost identical lawsuit against Broward County, Florida. One of the major reasons for the dismissal was that the ACS 5-Year estimates (the data for CVAP) was deemed not suited to accurately measure population—especially in rapidly growing areas (see p. 1208 of the decision). Sound familiar?

But here is the real kicker: the RNC did not choose these data sets at random. Both the CPS Voting Supplement and the CVAP—drawn, remember, for the ACS 5-Year estimates—are used regularly to measure potential violations of the Voting Rights Act and many other discussions of minority vote participation. The kind of analysis I did about the difference in percentages in Citizens over 18 in the various regions, for instance, is similar to what the CPS and CVAP can be used for in voting analysis. If the RNC lawsuit is rejected because these datasets are fundamentally unreliable, what does that say about other voting lawsuits based on the same data?

Finally, there is the fact that these datasets widely are used for policy decisions. If we cannot rely on them to provide accurate data for political decisions such as voting registration, why are they acceptable to use for determining unemployment policies, infrastructure needs such as schools and hospitals, or a range of other issues?

Nuisance or not, the RNC lawsuit (and those in other states) might have flagged some real issues in the data we collectively use to guide our society. That is a problem.