Rurals of Nevada: The Aging Rurals, Part 2 (art. 05)

"Nationally, 1 out of every 7 students . . . is enrolled in a rural school district. In Nevada, 1 out of every 11 attend." - The Guinn Center, "Rural Education in Nevada", August 2020

The Craftsman-style Midas School opened in this remote mining valley of western Elko County in 1927. Funded by a town bond, the school was described by state officials as “modern in every respect” down to the state-of-the-art outhouses. As Midas boomed in the 1930s, the one-room school served 30-40 children a year. The collapse of the local mines in the 1960s led to its closure by the Elko County School District in 1972 and the building was sold off. When the mines re-opened in the 1990s, the 200+ miners left their families at homes elsewhere rather than moving back to Midas. Eventually, the Friends of Midas bought the building and added it to the Register of Historic Places in 2004. Unfortunately, a fire a year later destroyed the building, leaving only the playground equipment and the outhouses.

As I mentioned in last week’s article, people are often surprised when told that northern rural counties such as Elko and Humboldt are the youngest in the state. After the initial shock passes, the first response usually is “well, you do have all those miners.” And this is where the median age measure fails: it is unclear whether the age is the result of an active, growing population (i.e., many children) or just a statistical result of large numbers of people in their 20s to 40s employed by the mines—who are likely to leave if the mines shut down.

The common reaction I just described reflects the continued hold of the “aging rurals” myth, particularly that there is nothing to hold people in rural areas except for one or two key industries. Grown children who don’t want to work in the industry leave. And if a county loses the industry, they lose its population. And if the industries come back, they are less likely to result in families coming back. In other words, rurals are doomed to age because younger people do not stay around and have families.

The history of the Midas School (minus the fire) is typical of many rural schools built in the early 20th century: no longer needed because there are fewer children likely in the future. The quote at the top of the page from the Guinn Center that Nevada has even fewer children in rural areas than the U.S. average appears to confirm this—even if unintentionally. The statistics say there just are not a whole lot of children in the rurals.

But what does the data say? The first approach is to look at whether there really are children in these counties. The most accurate measure currently available to look at this is the recently completed 2020 Census. Although only a limited dataset, the Public Law 94-171 Summary File, has been released to date, it has one vital measure for this discussion: the population under 18, derived from the population over 18 used to determine voting populations for re-districting.

Although this number is not directly relatable to school enrollment per se, it does provide a rough measure of the number of children in an area and can provide a useful corrective to understand what the median age in each county might mean. Let’s see what this tells us.

Under 18 Years Old in Rural Nevada

One of the major news stories from the release of the 2020 Census was that the United States was growing older. What the Brookings Institute’s William H. Frey called “a pronounced aging of the population” may have underlined many of the most significant changes unveiled by the Census, including stalling growth, a lack of geographic mobility, increasing diversity limited largely to cities, and rural areas being older and whiter. So how does Nevada compare to this overall assessment?

The good news is that Nevada actually fared better than the country as a whole. The 2020 Census showed the United States had 22.1% of the population under 18. Nevada had almost a percent more, at 22.9%. In itself, this is not surprising given that Nevada was one of the top five states for growth in the country. And if the majority of the population is in Las Vegas, Las Vegas must be the youngest part of the state and is pumping the youth numbers up.

Not quite. As always, let’s look at the breakdown of major areas within the state. We start with the three urban areas and the 14 rural counties considered collectively. The table below shows the population under 18, the percent of the population under 18, and the percent of the Nevada population under 18 in each region.

In many ways, this information is not surprising. Clark County is younger than the other regions of the state and has over 75% of the population under 18 in the state. Definitely a young, urban area. The other regions are older—but not quite in the same way as we saw last week in discussing median age. Washoe, for instance, was barely older than the state median age but has rather fewer children under 18. And Carson City, which is between Washoe and the 14 rural counties collectively in median age, has the smallest percentage of children under 18. The relatively younger median ages of Washoe and Carson City likely reflect a large population of early- and mid-career professionals.

This leaves us with the real surprise from this chart—the other 14 rural counties. Although they have an average median age of 45.0 years—by far the highest in the state—they actually have more children under 18 than expected. Indeed, they have a higher percentage of children under 18 than Washoe County, which includes Reno and Sparks.

As readers might have guessed, this situation gets even more complex once we break the data into the three rurals I am trying to define. Using the same three categories (and the same 2020 Census data) from the previous table, here is what the Three Rurals look like:

As in the case of median age, the Central Rural counties emerge as among the oldest in the state, with even a smaller percentage under 18 than Carson City (although they have slightly more children by number). But the Western Rural region is not far behind, well below the state level and having two of the three counties with the smallest population under 18: Storey has 15.1% and Douglas has 16.7% (Nye is in the middle with 16.5%). However, Lyon (22.1%) and Churchill (22.5%) balance this out somewhat with under-18 populations between the state and national average.

Once again, as in median age, the I-80 Corridor counties are surprisingly young, exceeding the state percentage in under-18 population by 4 percent (26.9%)—which is 7 percent more than other rural regions. In fact, if we look at the five counties which had under-18 populations higher than the Nevada state level of 22.9%, three of them are in the I-80 Corridor: Elko (28.5%), Humboldt (26.2%), Lander (25.4%), followed by Lincoln (24.1%) and Clark (23.6%).

Lincoln County is striking in its inclusion. It has a median age (per the 2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimate data) of 43.7. Although slightly less than the collective rural average of 45.0 (and much younger than neighboring Nye County at 53.1%), it remains older than adjacent Clark and even White Pine County to the north. The reason is not entirely clear and will require more research. I suspect that Lincoln’s young population might be established families with adolescents who moved into the Alamo / Pahranagat Valley US 93 corridor as spillover from Las Vegas’ growth, similar to the emergence of Pahrump as an exurb in Nye County.

For Elko, Humboldt, and Lander Counties, then, the low median ages discussed last week appear to reflect a much more balanced age distribution than just young miners or professionals. Larger numbers of families are in the area. And even though Eureka has a smaller population of under-18s, it is close to the United States average (at 21.9%), meaning a decent portion of its median age is accounted for by children as well.

Pershing has a much lower under-18 population of 18.6%, despite its median age being almost exactly the same as Eureka. This difference likely indicates Pershing’s families are living elsewhere, probably due to the lack of housing. The current efforts to expand housing in Pershing and Eureka might result in population booms as families are able to move into the area. In any case, the importance of the surging mining industry into these areas is not just bringing young miners but also their families.

The Diversity Issue in the Three Rurals

During the release of the 2020 Census data, the major news sites covered the diversity issue heavily. The main takeaway was that younger populations lived in urban areas, were more diverse, and were having more children. This added a wrinkle to the “aging rurals” debate by asserting “non-diverse” areas with majority white populations are less likely to have large numbers of children running around.

Yet the relationship between diversity and aging directly is hard to establish. The new use of a “diversity index” by the Census Bureau based on the proportions of various racial categories captures a snapshot of the situation at any given time (the formula is given in the link). The model, however, appears to me to lack explanative virtue on its own for many uses—including the aging of counties. There certainly is some correspondance, but what does this mean in terms of whether a county is aging or not?

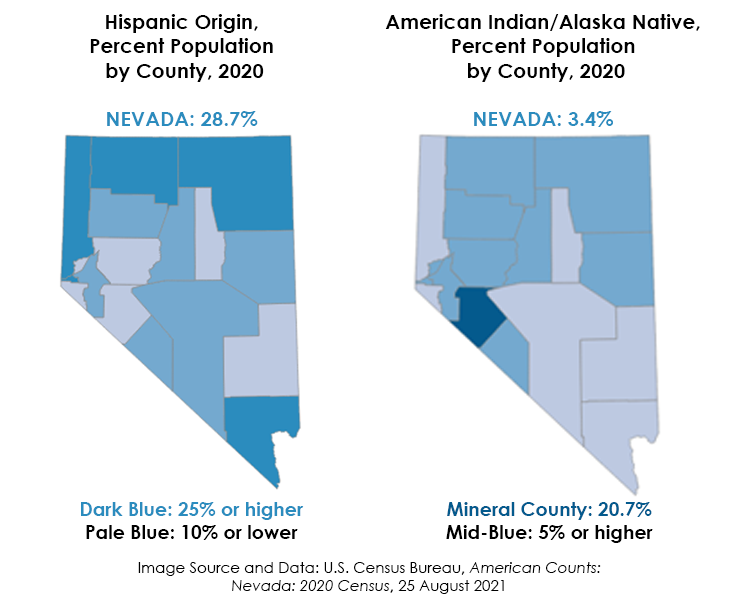

So, rather than using the diversity index on its own, I want to briefly look at the two largest minority groups in the rurals, Hispanics and the indigenous American Indian population (“American Indian/Alaska Native,” or AIAN, in Census parlance). The Census Bureau’s very well done “State Profile” page for Nevada released in conjunction with the redistricting summary file we have been using provides an easy tool to generate some useful statistics quickly. I put the maps of the county distribution side-by-side in the image below:

On the left is the Hispanic origin as a percent of the total county population. Nevada’s overall percentage is 28.7% Hispanic, although it is not evenly distributed. Clark County is approaching almost a third of the population identifying as Hispanic (31%). Then the percentage drops off sharply across most of the state until the northern three counties, Washoe, Humboldt, and Elko, all with over 25% Hispanic population. Lander and Pershing Counties also have large Hispanic populations of over 20%, higher than the rest of the rurals. So the Hispanic origin population in Nevada is concentrated in Clark and the northern counties.

The map at the right shows the same information for the AIAN population. The issue here is more complex, since as a racial category AIAN identification tends to mixed with other measures (and do not confuse this with tribal membership, which is an entirely different concern). Hispanic origin is a yes-or-no question currently, which certainly makes calculation easier. I am planning to look at this more in-depth in the future, but for right now the map is based on the combined category of “AIAN alone or in any combination.” The total percentage of the Nevada population who identify as AIAN, is 3.4%.

Certainly, by number, the majority are in Clark County (more than 50,000 and mostly from non-Nevada tribes)—but it is only a small fraction of the total population there. Washoe is somewhat similar, although with a higher percentage of Nevada tribes such as the Pyramid Lake and Summit Lake Paiutes, the Washoe, and the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony (a multi-tribal community). We will have better data coming in the summer of 2023 with the next big 2020 Census data release.

In terms of percentage of population, however, it is the Nevada tribal communities that are the most significant in the rurals. As I discussed in the article on the 2020 Midterm Elections, Mineral County is the only county where American Indians are the majority minority, 20.7% of the population, almost all from the Walker River Paiute Tribe. But 9 of the other 13 counties have AIAN populations exceeding 5% of the total population. Only Douglas, Eureka, Lincoln, and Nye Counties have smaller percentages in the rurals.

Both Hispanic and Nevada Tribes are important parts of the population in the I-80 Corridor counties—but they are not the majority of the under-18 population any more than they are the majority of the total population.

The key takeaway here is that both sets of minorities are found well represented in the I-80 Corridor counties—except for Eureka. Eureka County is the second least diverse county in Nevada (Lincoln is first), with 85% of the population identifying as White. And this brings up an important point: despite the high proportion of minorities in the I-80 Corridor counties, they are not the majority of the under-18 population.

Since the re-districting data does include racial and ethnic breakdown of the total population and the voting age population, we have good information on this distribution as well. For the Hispanic population, they comprise 41.0% of the under-18 population in Clark County, and 38.5% in Washoe. The other three counties with Hispanics more than 30% of the under-18 population are, in order, Humboldt (36.3%), Elko (32.8%), and Pershing (31%)—all in the I-80 Corridor.

The Nevada tribal numbers are harder to come by, but given the relatively low population percentages overall, they might be adding from 1-5% of the under-18 children, depending on the criteria used. Mineral County is the one exception, although it is outside the I-80 Corridor.

Taken together, then, the under-18 population in the I-80 Corridor is spread much more evenly among the three groups (white, Hispanic, American Indian) than in the urban areas. So diversity is a key indicator, but in itself not a cause. Indeed, in most of this area the white under-18 population was at least 60%. That percentage is almost exactly the same as the overall white, non-Hispanic share of the 2020 population of the United States of 63.7%. The I-80 Corridor looks a bit more like the country as a whole than the rest of Nevada.

Some Conclusions

The Three Rurals do not share one single model of youth or lack thereof, as evidenced by the wide range of median ages and under-18 populations among them. They are experiencing different issues with young and old populations in ways that will require different policy approaches ill-served by assumptions of the “aging rural” myth.

The range differences in the median ages and under-18 populations among the Three Rurals indicate they are dealing with young and old populations in different ways, all ill-served by policies based on the assumption of a single “aging rural” myth.

Economics, I think, places a significant role. The expansion of mining and the potential economic diversification of Elko is creating new opportunities in the I-80 Corridor which are not only bringing in white and Hispanic families, but also working to keep Nevada tribal families located closer than their homes rather than seeking opportunity elsewhere. Here, diversification is a by-product of the “younging” of the population and diversification of the economy, not a cause.

The Western Rural counties are doing well economically, but with the exception of Churchill and perhaps northern Lyon County are showing neither explosive youth growth nor diversification. They are aging, but with more balanced (and perhaps more stable) populations. They are also benefitting from the proximity to the Reno-Sparks-Carson City complex, developing suburban and exurban characteristics.

This is in sharp contrast with the Central Rural counties. These are the stereotypical “aging rurals” which are struggling with dependence on mining and few other options. Merely bringing back mining without the infrastructure developed as it is currently being done in Elko might not help them in the long term. Nor is any good prospect clearly on the horizon that I can see.

These differences are also why I did not discuss what many people assume is a good dataset for discussing youth policies: school enrollment. These numbers are vital but also rather narrowly descriptive rather than explanatory. Debates over school funding formulas have roiled Nevada politics over the last decade—most of it concerning whether rurals “need” the higher levels of funding or whether it should go to the larger number of children in Las Vegas. This is an important debate which I currently am not gluttonous enough for punishment to try to enter other than to say that some of the rurals, at least, may have greater need for funding in the future beyond what current and projected enrollments indicate.

The real question to be answered, however, is the extent to which this population of children represents a true measure of the “youth” of certain rural counties or merely a temporary bump from economic opportunity which, when dissipated, will see these counties return to being old, aging rurals. In other words, how sustainable and predictive are these changes? That is the issue with which this set of articles is grappling.

To answer it, however, we need to perhaps look at the other end of spectrum: the aged part. That will be the topic for next week.

One minor note. On Thursday, 8 December 2022, the Census Bureau will be releasing the 2021 American Community Survey data, including the 5-Year Estimate for 2017-2021. I plan in the future to look at this more in-depth, but it may be after the holidays before I can give a comprehensive update.

Thank you again for reading, and please feel free to share with others who might enjoy or at least tolerate my ramblings.