Where has and Where is Rural Nevada Growing? (The Rurals of Nevada art. 21)

Before getting into the specifics on how Nevada's rural population is changing, some baseline background information is needed. And lots of graphs.

I have been wanting to dig into some of the population data from the 2024 edition of USDA’s Rural America at a Glance, as I mentioned in the last article. In particular, the argument that rural counties are starting to grow again—albeit by migration rather than natural increase—is an intriguing conclusion of the report. So examining if this was the case in Nevada appeared to be a good place to start.

But as I have started playing with data, it occurred to me that one of the problems with looking at the Rural America at a Glance data is that it is a year-to-year change. Such a chronological focus has its uses. but can hide some longer-term trends developing. For instance, the growth of nonmetropolitan counties that reversed a long-standing decline was barely evident in the 2023 Rural American at a Glance (see page 2) and then picked up speed. But did that hold here in Nevada as well?

Of course, the Census Bureau has population data going back decades. However, for the purposes of the next few articles, I will focus on the period from the 2010 Census forward. A few reasons for doing this. First, going with 2010 allows me to work with two decennial Census datasets, that of 2010 and 2020, which serve as baseline counts. Secondly, we move past the perturbations of the Great Recession of 2008. Finally, the period also fully encompasses the use of the American Community Survey (ACS) data if needed, since the ACS was implemented only in 2006.

Primarily, I will draw on a dataset I have not really discussed before, the Population Estimates Program (PEP). This program estimates the population of the United States, states, counties, cities, and towns as of July 1st of every year, based on an estimation model developed after each decennial Census. The estimation model is used until the next decennial Census where the actual population count is used to devise a new model. The PEP has also added annual housing unit estimates (which I suppose technically makes it PEHUP). The basics are given on the Census Bureau’s About page for the PEP.

Three factors make this dataset directly relevant to what I want to examine. First, the PEP is a yearly estimate and therefore provides more consistent data than the ACS for our purposes. Second, it also collects factors in change, such as the number of births, deaths, and migration; this will be useful in future articles. Finally, it is what the USDA Economic Research Service uses for its yearly analysis of population change in Rural America at a Glance. Apples-to-apples and all that.

While the Census Population Estimates Program (PEP) provides some consistent, yearly data, analyzing the

Naturally, comparing population numbers directly would be rather pointless; the sheer scale difference between urban and rural growth would make comparisons difficult. But we can use the percentage growth rate, which would at least put the information legibly on the same graph. But even then, the variation from year to year might present some issues of interpretation as percentage change moves up and down. What I’ve done is to look at cumulative growth since 2010, effectively zeroing the data for that year. The cumulative growth rate from 2010 through 2023 provides a long enough period (13 years) to see any long-term growth trends.

Nevada’s Growth: The Big Picture

Now that the dataset is worked out, we can begin looking at the growth patterns. One of the biggest stories coming out of the 2020 Census was that the fastest-growing states were in the West and the South, indicating a rather significant change in the distribution of the country’s population (see this 2021 U.S. News and World Report article for some perspective). Nevada was ranked as the 5th fastest-growing state in the country between 2010 and 2020.

So what does this growth look like from the perspective of the PEP data? Figure 1, below, presents Nevada’s cumulative growth rate since 2010 (solid blue line with no markers) compared to U.S. growth (gray dashed line) from the same period. Also included are the cumulative growth rates for the three urban counties (orange line with triangle markers) and the 14 rural counties (green line with circle markers).

The divergence between Nevada’s growth rate and that of the United States starting in 2012 is evident in the graph. By July 2023, Nevada’s cumulative growth rate since 2010 (18.3%) was more than double that of the United States (8.3%). The departure starting in 2012 most likely represented the end of the state’s struggles from the Great Recession of 2008; note that Nevada’s growth was below that of the country in 2011. It then became caught up in the increased westward growth that marked the 2010s.

Undoubtedly, the growth in the three urban counties (Clark, Washoe, and Carson City) was a primary driver, often slightly exceeding Nevada’s rate while mostly paralleling it. This fact is unsurprising given that over 90% of Nevada’s population is in those three urban counties. By 2021, they were growing just under 10% faster than Nevada as a whole. On the surface, this supports the model that urban areas are largely responsible for whatever growth does occur.

However, the distinctly different shape of the 14 counties in the Rurals of Nevada requires a more thorough explanation. The rurals lost population before rebounding to positive growth after 2012—so somewhat similar to the timeframe of the urbans. But rather than accelerating, growth stayed relatively flat until 2016. After that, the rurals rapidly began to grow, but at a much slower pace than the urban counties.

It was only in 2020 that the rurals surpassed the United States’ growth rate. Note, however, the rather marked jump in the rurals’ growth line between 2019 and 2020. This is not a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, but rather the adjustment to the population model from the 2020 Census totals. Remember that the PEP is adjusted by each decennial Census, which represents an actual total count of the population rather than a statistical model estimate. By jumping up, it means the population estimates before 2020 were likely underestimating the population in the rurals of Nevada.

The jump in the Rurals of Nevada’s growth between 2019 and 2020 was likely not a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, but a correction resulting from the previous Census model underestimating the rural population, which was corrected by the 2020 Census.

The difficulties in counting smaller rural populations is been a consistent problem discussed here, and the growth rates illustrate that. Note there is also a slight flattening in the growth curve for the urban counties, likely meaning they were slightly overestimated in the previous decade. Again, this is a result of having more complete data for large metro areas. The impact on growth rates, however, is a bit more muted because of the larger initial population size.

Trying to calculate the precise undercount percentage would require far more time and understanding of Census methodology than I have at the moment. It does mean, however, that the rurals’ growth was likely somewhat higher than shown. My guess is that it surpassed the U.S. growth rate around 2018 or 2019—and perhaps slightly earlier.

The takeaway in that sentence is that rural Nevada has surpassed the U.S. growth rate for a number of years. That in itself is news considering. And since 2020, the rural population has continued to grow fairly consistently. For Nevada, at least, the growth that the 2023 Rural America at a Glance noted had started well before 2023.

Growth of the Three Rurals of Nevada

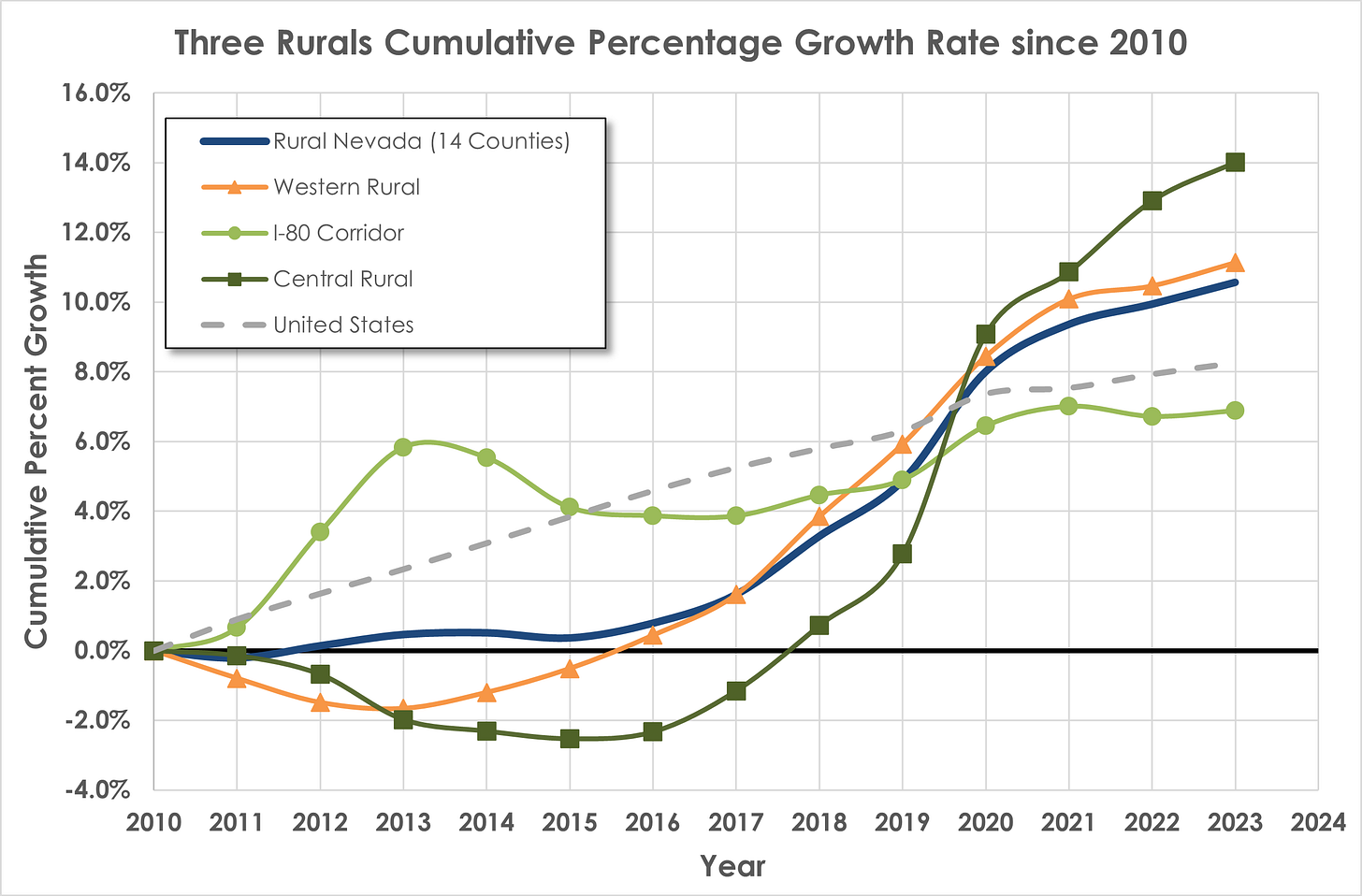

It would be surprising if this growth in the 14 rural counties was consistent, and indeed it is not. We can begin by looking at each of our Three Rurals of Nevada as a whole. Figure 2 provides the growth rates for these areas compared to the growth rate of the 14 rural counties as a whole (solid blue line with no markers) and the United States growth rate as a whole (gray dashed line).

Not a single region closely followed the combined rurals’ growth rate. The Western Rurals (Churchill, Douglas, Lyon, and Storey counties) come closest, especially after 2017 (orange line with triangle marker). However, they experienced a rather sharp decline in population until after 2013, and only moved into positive cumulative growth by 2016. After that, the Western Rurals—which, remember, account for around 50% of the rural Nevada population—mirrors the 14 Rurals growth curve closely.

The Central Rurals (Esmeralda, Lincoln, Mineral, Nye and White Pine counties) had an even grimer experience in the 2010s. They had significant population loss before reversing in 2016 (dark green line with square markers). But the most significant fact is the huge jump between 2019 and 2020—almost a 6% increase. Again, I highly suspect this is a result of a significant undercounting in the Central Rurals, the least-populated area of the state with the lowest population density.

Without that underestimation, I think the Central Rural growth rate would have looked very close to that of the Western Rurals—at least until 2020. With the decennial catapulting the Central Rurals over the Western Rurals and allowed them to surpass the 14 Rurals collectively, the growth rate continued to accelerate. The Central Rurals are the fastest growing region of the Rurals of Nevada. More on that in a minute.

The one exception was the I-80 Corridor counties. Despite a sharp increase peaking around 2013, the I-80 Corridor lost population and fell below the U.S. growth rate by 2015. Despite some periodic flucuations, the region never climbed back above the U.S. growth rate. More significantly, it has the smallest bump between 2019 and 2020, indicating it likely had the smallest undercount. Despite being the youngest area of Nevada, it just does not appear to be growing much.

What to make of these differences in growth? The Western Rurals are the easiest to explain as the delayed result of the urbanization boom of the early 2010 in the Reno area. Within a few years, the surrounding rural counties started to become commuting bedroom communities.

The I-80 Corridor counties on the surface seem to reflect what many would consider a rural extractive-industry-based growth pattern: fluctuations driven by mining but not consistent growth compared to other areas. Even the fact that it is the youngest area is explainable as children leaving as they become adults—the “hollowing out” effect of the rural myth. Yet data such as those I used to construct the population pyramids appears to refute this. Something odd is going on here.

And even more so with the Central Rurals. Most evidence indicates these five counties are the most rural of Nevada counties. They are also heavily dependent on extractive industry, even if not to the extent of the I-80 Corridor. Nor has the area generally experienced spillover growth from Las Vegas, Pahrump excepted (see the last article for details). Yet not only does the Central Rurals’ growth look more like the Western Rurals, it is surpassing them in rate of growth.

To answer these questions, we should dig a bit deeper into each region. Could it be that the growth rates are the result of different county issues that are interacting in unanticipated ways?

Growth Within the Three Rurals

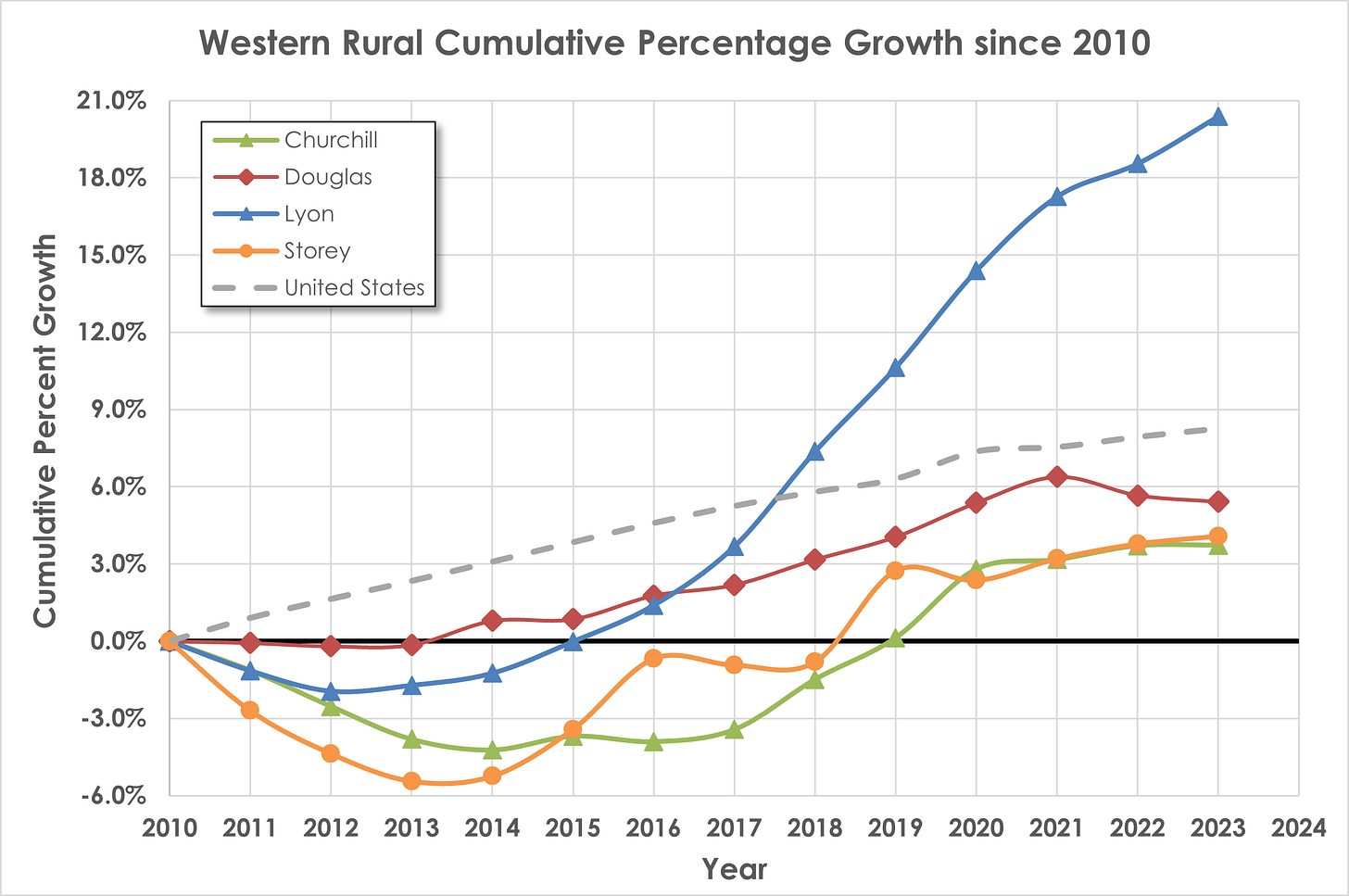

We can start with the Western Rural region—Churchill, Douglas, Lyon, and Storey counties. Located with the metropolitan radii of Reno and Carson City, it is not surprising that this area has one of the most active growth rates. Figure 4 gives the cumulative growth rates in the individual counties, again with the United States growth rate for comparison.

Despite their proximity to the Reno and Carson City, all of the Western Rural counties initially saw their population shrink after 2010. Douglas County began seeing positive growth first, around 2013, and them settled into steady growth rate that peaked in 2021 (I suspect this was the result of increasing retirement to the area). Both Churchill and Storey counties had a steady decline in growth before starting to grow again (after 2014 for Storey and after 2017 for Churchill). Both counties started to experience roughly the same, albeit slow, growth after the 2020 Census, with Churchill having a noticeable bump between 2019 and 2020, again indicating underestimation. While continuing to grow, all three have remained below the average percentage growth of the United States as a whole.

Lyon County, however, is a totally different story (Lyon is the blue line with the triangle marker). Recovering growth soon after Douglas County, Lyon accelerated and never stopped—and is continuing to grow. It surpassed the U.S. growth rate in 2018—the only county in the Western Rurals to do so. Lyon County’s growth since 2016 has almost single-handily made the the Western Rurals exceed the U.S. cumulative growth rate.

A more pronounced variation of this pattern occurs in the Central Rurals—Esmeralda, Lincoln, Mineral, Nye, and White Pine counties. Note the vertical scale in Figure 4, which now expands from -20% to +28%. That is almost a 50% difference in cumulative growth rates. Obviously something unusual is going on.

First off, I would put no credence in the variations of Esmeralda County’s growth. With a population of well under 1,000, any variation is going to be magnified. And note the sharp drop between 2019 and 2020. Esmeralda County actually was most overestimated county in Nevada—meaning its population was even smaller than the estimates gave.

But it was hardly alone. In fact, except for a small positive bump in White Pine County with the mining mini-boom in the early 2010s, all of the Central Rurals lost population until 2016. Even after then, White Pine lost population and even the modest growth in Lincoln and Mineral kept them from recovering to 2010 population levels. Moreover, Esmeralda, Lincoln, and White Pine counties were being overestimated; note the sharp drop in population between 2019 and 2020. Mineral County had a small increase which may indicate an underestimation (I suspect better Census results from the Walker River Reservation, Mineral County’s youngest area, were the factor here).

The exception is Nye County. Nevada’s largest county (blue line with triangle markers) began growing in 2014 and never looked back. The sharp increase between 2019 and 2020 indicates the massive extent to which Nye County had been underestimated before the 2020 Census. But where is this population growth coming from? In a word, Pahrump. The Pahrump Census County Division (CCD)—remember that Pahrump is an unincorporated town—contains over 86% of Nye County’s 53,200 population (U.S. Census, 2023 ACS 5-Year Estimate, Table DP05). Nye County’s population increased by roughly 10,000 people from 2010-2023 while Pahrump’s population increased by . . . roughly 10,000 people. You do the math.

The final of the Three Rurals is the I-80 Corridor, comprising Elko, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing counties. This region is very different from the previous two, making it much harder to explain. This has a lot to do with the more rapid flucuations in population, as shown in Figure 5, below.

Although one could dismiss Eureka’s up-and-down pattern as similar to Esmeralda’s—that is, the result of a very low population magnifying the impact of even small changes—it should be noted that all the counties show more fluctuation than the other regions. This is obviously a result of nature of mining where expansion and contraction of mines can result in dramatic swings in population. The most notable example of this is the pronounced bump peaking in 2012, then a loss of population until another uptick leading into 2020. Compared that with the this 2022 image of gold prices and Nevada mining production from the Nevada Division of Minerals.

But notice the different experiences starting in 2020. Eureka saw a dramatic decrease between 2019 and 2020, undoubtedly the result of earlier overestimation across the decade. But both Humboldt and especially Lander had increases, indicating their populations had been underestimated. But then their experiences diverge, with Lander County stabilizing while Humboldt sees another peak in 2021 before decreasing. Pershing County is an outlier here; its growth appeared to be on the decline before the 2020 Census. There has been a lot of discussion about Pershing County’s problems of development in the last decade, including a massive lawsuit of Humboldt River water usage against upstream counties (Humboldt, Lander, and Elko), that parallel this lack of growth.

The one county that has increasingly escaped this dynamic is Elko County. As I’ve noted in previous articles, Elko is unusual in that fewer mines are located in Elko County even if the miners are. While Elko clearly benefitted (and then suffered) from the mining boom of 2010-2012, it displays a distinctly different pattern afterwards. It grows steadily and at a higher rate than the United States as a whole—the only county in the I-80 Corridor to do so. I would also note that this development parallels the shift after 2015 in Elko County’s economy to a (slightly) more diversified one of services rather than mining directly. Elko County is developing differently from the rest of the region.

Conclusion: The Single-County Paradox

It is fascinating that the pattern of all growth in these regions is tied to the growth of a single county which is the only one in the region that exceeds the United States cumulative growth rate. This single county paradox has some interesting ramifications. First, it rather indicates that the notion that growth tends to be associated with developing metropolitan or proto-metropolitan areas with diverse economies is correct.

Secondly, it makes regionally-oriented policies nightmarish. For example, what does Pahrump’s growth mean for policies to help the rest of Nye County or the Central Rurals generally? Does it mean that housing development funds, for instance, be directed solely at the explosive growth of Pahrump while the rest of the region (such as Tonopah and Goldfield) “make do” with decaying building infrastructures? Should Pahrump’s relatively easy access to Las Vegas capital and construction markets factor into this consideration? What about Elko, largely isolated by distance from Las Vegas and Reno capital and construction markets? Should it be given a different priority than, say, Fernley in Lyon County?

Finally, one last graph indicates that there are still some profound differences that need to be examined. Figure 6 shows the cumulative growth of the three Single Counties (Elko, Lyon, and Pahrump) with each other, Nevada’s growth, and that of the United States.

Note that the sharp growth in both Lyon and Nye counties is a relatively recent development. Both only passed the United States growth rate and that of Elko County after 2017. And both show a distinctly sharp uptick in growth. Elko County, however, exceeded the U.S. growth rate in 2011—and has largely parallelled it ever since. This indicates that a different pattern of growth is at play than in either Lyon or Nye.

That will be the focus of future articles. Thank you all again for reading!

Thank you, this is a wonderful analysis!