Rurals of Nevada: The Aging Rurals Revisited-- 2020 Census Population Pyramids (art. 16)

Digging into the 2020 Census detailed age statistics and playing around with population pyramids as a means to look at demographic differences between regions.

After a long hiatus for work, family, and medical issues, I have finally been able to start digging into the more detailed 2020 Census data. Since last May, there have been numerous data releases from the U.S. Census Bureau. Even though we are more than three years since the Decennial Census the data collected represents an actual count, rather than the estimates of the American Community Surveys. And I am sure that data.census.gov is being inundated with users seeking information (like me!).

To start, I remain fascinated by the question of age across regions. Regardless of what I examine—economics, general policies, schools—the issue of age is always intertwined. Age is also central to the “rural myths” I have examined (see in particular The Aging Rurals series). Delving into more detailed age data is a good start.

My previous looks into the age dynamics focused on large population measures: Under 18, Over 65, and median ages. However, a detailed age analysis will require far more categories. It also presents a presentation problem: how to present information without readers having to follow along with a massive table listing all ages for each region. Not to mention how to post something like that on Substack.

But a readily available visualization might be useful: the population pyramid graph. Most people are familiar with the concept: age cohorts (usually of 5 years) stacked to give a roughly pyramid shape providing a glimpse at the population in toto. These graphs are so popular the U.S. Census Bureau released a nifty tool back in May to generate them (scroll to the bottom of the article for the tool). Here is the population pyramid generated for Nevada:

The population pyramid is popular because it provides at a glance varied and significant information. Not only is the current population readily apparent, but projections can be made. For instance, knowing the number of children Under 5 can provide a predictive measure of how many elementary school places are going to be needed over the next decade. Likewise, projections of retirees allow both pension plans and geriatric practitioners to anticipate needs. Even the shape of the graph—does the pyramid point up, down, or something in between—can be informative of the trajectory of a population. Quite a bit of lifting for a simple graph.

Playing Around: Population Pyramids and Regions

Despite these advantages, traditional population pyramids are not entirely suited to the regional comparisons I am doing. I am less interested in the male/female divide than the differences between regions. Nor would just presenting separate pyramids for each region solve the problem, as it would result in requiring readers to dart back and forth and interpellate my meanings.

But comparisons are comparisons, right? Since the population pyramid usually contrasts male-to-female populations, why can’t other categories be inserted? We can try by comparing regions in place of the male/female.

For the statistics, data.census.gov comes through again! For ease, I am using Table DP1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. For those who would like to play along at home, just type “DP1” in the search bar, and it will be the first item listed. If you “View all 11 products,” just choose “2020 DEC Demographic Profile” to get all the states. The “Geos” tab at the top will also let you explore counties and other geographies.

Here are the basic changes I am making to the common population pyramid model beyond just getting rid of the male/female categories as a basis:

Since we are dealing with regions of different population sizes, I am going to use percentages of the population rather than numbers.

Table DP1 groups those 85 and older into a single category. This flattens out the top of the pyramid but maintains the rest of the shape—which is the primary area of concern here.

In all of these graphs, the left side is the first region named while the right side is the second. I am adopting the convention of placing the larger populated region on the left to serve as a point of comparison.

With these in mind, we can start the experiment by comparing the United States and Nevada with each other to give a nice baseline.

In this comparison, there is not much difference between the United States (again, in gray on the left) and Nevada (in blue on the right). Both show the “stationary” distribution of most age ranges for adolescents and adults, typical of mature developed countries where fertility and mortality have balanced out for decades.

Naturally, there are some differences. Nevada has noticeably fewer people in the 15-25 cohort. My suspicion is this fact is due to more limited post-secondary education options in Nevada as well as a tendency of Nevada youth to enter military service. Nevada also has a smaller percentage of its population 80 years old and older. This difference is not surprising given Nevada’s low population and, shall we say, erratic healthcare coverage.

But both are also showing a smaller percentage of children under 10, indicating that the United States and Nevada have entered a demographic transition where the fertility rate is falling below the replacement rate. The resulting graph has an oval shape, tapered towards the older segment of the population. Indeed, this fact was the purpose of the U.S. Census Bureau article which featured the nifty tool above: “An Aging U.S. Population With Fewer Children in 2020.”

As a digression, does this mean we need a different name than “pyramids”?

Taken all together this graph reinforces a consistent pattern of similarity between the United States and Nevada. This correspondence occurs among many different topics. If nothing else, it adds support to Jon Ralston's #WeMatter campaign to promote Nevada as representative of the nation for political purposes.

Nevada Population Pyramids: Urbans vs. Rurals

As always, I am interested in in how different regions of Nevada compare to the state as a whole.

We can begin by comparing the state of Nevada with the three urban counties collectively. Recall for my arguments these three are Clark, Washoe, and Carson City. Together, they comprise over 90% of Nevada’s population and therefore would have a correspondingly large impact on Nevada's overall demographics. Note that Nevada, as the larger region, is on the left (in blue) in the resultant graph as the basis for comparison.

Indeed, we see very few differences between the state of Nevada as a whole and the urban counties. The urban counties have slightly more even proportions of young adults (20-25 years old) and 40-45-year-olds, but not a significant difference. From a demographic perspective, the state is defined by the urban populations.

So how do the other fourteen counties—Rural Nevada—compare to the state as a whole? With less than a tenth of the state population, any specificity of rural demographics becomes lost in the state-level data. When we just focus on the data for these counties, we get the following:

Well, that is . . . different. Rather than the oval, the rurals have a concave structure. Although the levels of children from ages 0-14 are not much different from the urban counties, the population percentages decline drastically into adulthood. Even the 25-39-year cohorts—the younger miners and professionals who often are assumed to be the source of the “youthfulness” of rural communities—are a smaller percentage of the population than in the urban areas.

But once we get to those 55 years old or older, the situation changes dramatically. These age cohorts comprise a much larger percentage of the rural population than the same cohorts do of the urban population. The “senior citizen” contingent is the largest component of the rural population. The upper part of the graph mimics the “constricting” inverted pyramid associated with demographic decline as the population falls below the replacement rate.

In short, this graph illustrates two of the core components of the “Aging Rurals” myth. There is a “hollowing out” of the working-age population, particularly for the 20-24 cohort. In addition, an unusually high number of senior citizens exist. The only exception—significant, in my view—is the slightly larger percentage of children in the rural counties.

Population Pyramids of the Three Rurals

The main argument of this series is that three different “Rural Nevada” exist. Do they each follow the same rural population period as above? Another pertinent question that follows is where are the children located. Is rural Nevada beating the “Aging Rurals” childlessness or are the children concentrated?

We can begin with the most highly populated rural region, the Western Rural comprising Churchill, Douglas, Lyon, and Storey counties. These four, united primarily by their proximity to the Reno-Carson City urban area, had just under half (47%) of the rural Nevada population. They therefore exercise an important influence on rural demographics—but not to the extent that the urban counties exercise over the state.

First, notice a very important change: the percentage scale at the bottom is different. All the rural regions have age cohorts exceeding 8% of the population. In other words, the demographics in the rural counties concentrate on certain age cohorts. This change does flatten the graphs somewhat, although the vaguely oval shape (kite-shape?) for Nevada is still evident.

More significant is the shape of the graph for the Western Rurals. In every age cohort until 55 years old these four counties collectively have a lower percentage than the state as a whole. This fact also reduces the hollowing-out dynamic—although the notable decrease in the 20-24 age cohort is quite apparent. But once the senior citizen cohorts (55 and older) are reached, the population explodes dramatically to comprise just over 40% of all inhabitants.

This same pattern is more evident in the Central Rural region. Covering Esmeralda, Lincoln, Mineral, Nye, and White Pine counties, this is the least-densely settled part of Nevada and has about 24% of the population of the fourteen rural counties.

Here, any hint of concavity is gone. Even the young adult (20-24 years old) drop-off is muted—largely because there is a much smaller number of children here. The population cohorts are roughly equal until 55. An astounding 45% of the Central Rurals’ population is 55 or older and over a quarter is between 60 and 74. I believe the technical term for this type of constrictive population pyramid is “yikes.”

One minor difference between the two regions is intriguing. Although both have significant populations older than 55, the cohorts are not the same. The Western Rural peaks in the 60-64 range with the ramp-up starting at about 50 years old. The Central Rural peaks five years later, in the 65-69 cohort, with the ramp-up starting at about 55. I speculate this difference comes from the Western Rural counties largely being “destination retirement” locations with people moving in as they reach retirement age and moving out later. The Central Rural counties, on the other hand, likely represent those who have retired in place.

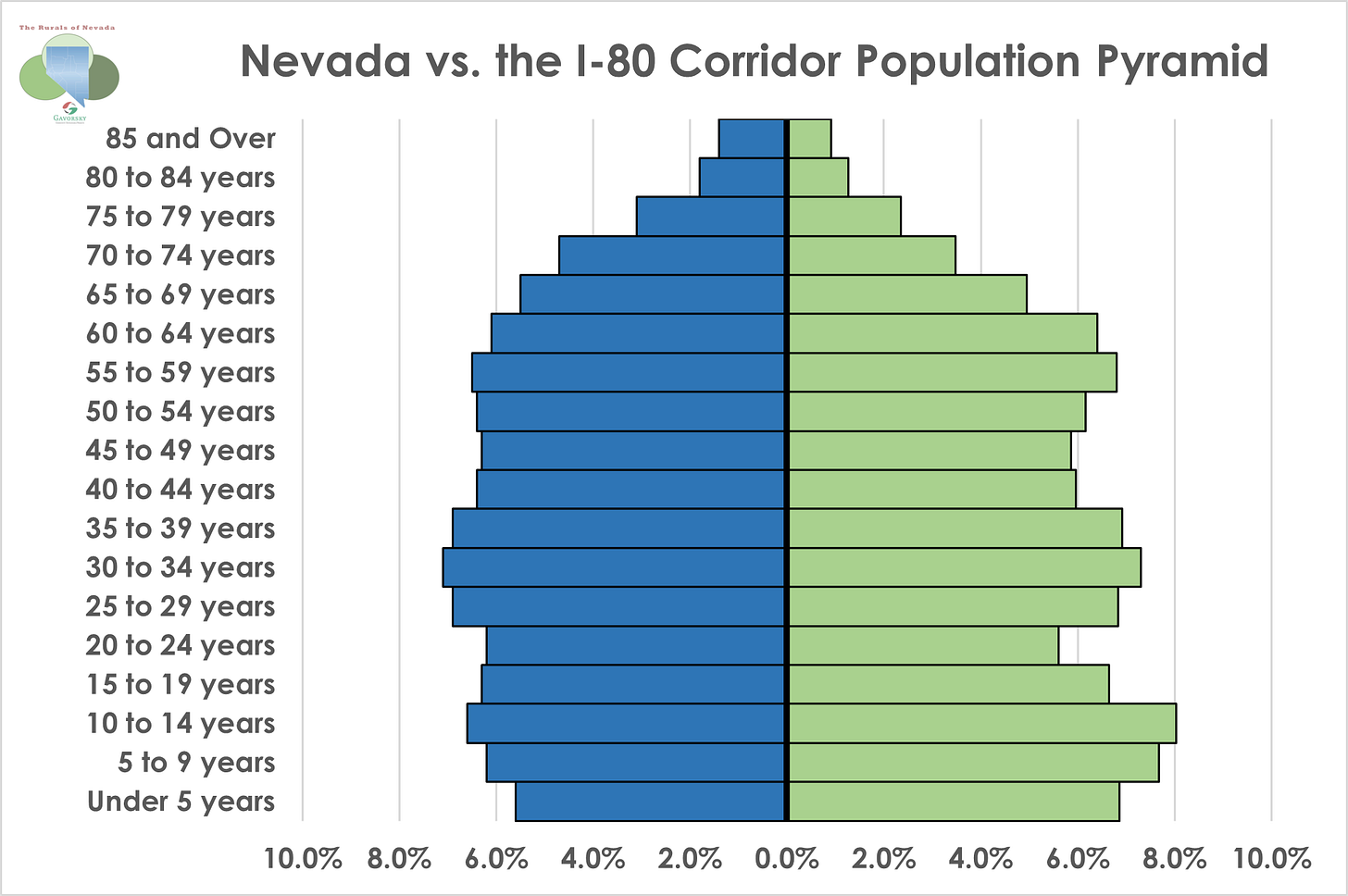

But note that both feature relatively fewer percentages of children compared to the state. We have still not answered the question we started with: where are the children? Enter the I-80 Corridor. This region comprises Pershing, Humboldt, Lander, Eureka, and Elko counties. A growing region and the current heart of the mining industry, these five counties comprise 29% of the total rural population. The region’s population pyramid looks distinctly different from the rest of Nevada:

Well, we found the children. The four youngest age cohorts (0-19 years old) comprise over 29% of the region’s population, slightly higher than its share of the rural population. Moreover, the 55-year and older population is just over a quarter of the total population (and peaks around 55, younger than the other two rural regions). These two factors together explain why the fourteen rurals collectively have a child population not too different from the state. The region also tapers off markedly for senior citizens.

But there are also some other points of interest. Notably, except for the expected 20-24 year olds, little evidence exists of hollowing-out compared to Nevada as a whole. Even the slight decline of mature working cohorts (40-49 years old) is relatively minor and not far behind the state. The senior citizen cohorts also diminish much more sharply than in other regions.

The result is a shape close to an expansive pyramid. It does not have a broad bottom representing many births (which is typical of expansive pyramids in developing countries). Yet it shows a type of growth—either from young families arriving or people born here staying—which is unique in the state.

Conclusions: Population Pyramids and Rural Populations

I do not expect my little experiment in using population pyramids to compare regions to catch on generally. The best use of population pyramids is for those in cities and counties to plan for the future. For these users, comparisons between regions are, at most, a secondary concern and will often be centered on a smaller number of peer regions.

However state-level analyses may find it useful to adopt a more nuanced view of regions. The fact that Nevada as a state mirrors the national situation while containing significant regions showing quite divergent population pyramids is a matter of concern. In short, state-wide solutions are not going to be effective given the spectrum of demographic circumstances across the state. For instance, promoting in-migration policies for both the urban counties needing workers and “hollow-out” rurals might appear to make sense. But what happens to those Nevada-born children in the I-80 Corridor? Is Nevada comfortable with them draining off to other states because preferences are given to others in recruitment?

I am not sure I have an answer, but it is a question that needs to be asked.