Deeper Red Rurals but Still Losing Senate Races (art. 19)

Once again, the specter of "blame the voters" emerges.

Another election is over, but the election season lingers. Ugh. Let’s get to it.

Following the 2022 Midterms and the lack of the widely-predicted “Red Wave” (is that trademark still pending?), I offered a tentative analysis of voting patterns in the Three Rurals of Nevada. The article was sparked by initial comments from Republicans that Adam Laxalt lost the U.S. Senate race to Catherine Cortez-Masto because rural voter turnout was down. That charge was incorrect—rural Republican voters in fact turned out in high numbers. It was rural nonpartisans—many of whom were registered automatically through the DMV rather than voluntarily registering—who did not vote and drove rural turnout numbers down. The commentators misread the data. As it turned out, Laxalt’s main problem was Washoe County.

We have had another election where the results were not as expected, and unsurprisingly, voters are back in the crosshairs of parties as the scapegoats. The Democrat charges are playing out nationally in an obnoxiously unseemly manner; I am not going to wade into that cesspit.

The Republicans have their own blame game going on, once again centered on the U.S. Senate race (plus ça change . . .). The worry this time is not rural voters per se, but the number of voters who went with third parties, particularly the Independent American Party (IAP) and its Senate candidate Janine Hansen. The argument is based again on a cursory read of the data: Hansen currently has over 20,300 votes, slightly less than Rosen’s margin over Brown of 21,400 votes. Moreover, Hansen’s total exceeds the IAP presidential ticket (Skousen-Combs) total by an astounding 17,900 votes. According to the blame game, those Hansen voters largely cost Brown the Senate seat.

Brown’s loss is due to factors evident in the data that point to a far more important concern with the American political system than third parties peeling off voters.

I am not so sure. I think there are other factors at work that are plainly evident in the data and that, in my opinion, point to a far more important concern with the modern American political system than third parties peeling off voters.

Plus, the argument gives me a chance to revisit my earlier article about voting patterns in the Three Rurals and see if the analyses there hold up. With a few years of reflection, the three main conclusions I reached in 2022 can be summarized as follows:

The 14 rural counties (remember, I do not include Carson City in the rural category) do not have enough votes to win elections outright, but can push candidates over the edge in tight races. This phenomenon is exactly what happened to give Joe Lombardo the governorship in 2022.

The Three Rurals are all deep red—but not in the same way. One factor relevant here is the impact of third parties. The Western Rurals (Churchill, Douglas, Lyon, and Storey Counties) tend to have fewer registered third party voters, more closely paralleling the binary divisions of urban areas. The I-80 Corridor (Elko, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing) and the Central Rurals (Esmeralda, Lincoln, Mineral, Nye, and White Pine) are more politically diverse.

The increase in nonpartisans driven by automatic registration at the DMV after January 2020 (“motor voter”) is creating a large pool of voters not likely to vote at all. In addition to driving down turnout rates, I am increasingly convinced this is leading election policy discussions in unproductive directions.

So, without further ado, we can begin digging into the most recent election data.

Voter Registration in the 2024 Election

I plan to leave analyses of the presidential contest in Nevada to those more knowledgeable and far above my pay grade (paging Jon Ralston . . .). I think no one was surprised that Trump carried the rurals of Nevada handily, with a 45.7% margin for the 14 rural counties collectively (again, not including Carson City) compared to the 3.4% margin in the state overall. In the I-80 Corridor, that margin was an astounding 57.5% (Trump won almost 78% of the vote).

True, the more than 15% of his votes which came from the rurals (over 109,000) added nicely to the margin, but the real story with the presidential race was Trump’s performance in the urban areas. Harris’ campaign did make a valiant effort in at least Elko County (although I do think whoever advised her to use that glaringly revolting shade of yellow on her billboards needs to be sentenced to work in an office painted that color for a year), but it was never going to make a major difference.

But the presidential race serves as a baseline for any discussion of turnout. Not only is the presidential race likely to attract the largest number of voters, it also serves as a comparison for candidates of the same party down ballot. Did those candidates do better or worse than the presidential candidate? Why or why not? So we can delve briefly into the presidential race just to position ourselves.

One brief note before starting. I am going to draw the information the Nevada Secretary of State’s reports. Note the plural—there are currently multiple reporting documents that do not totally line up. Of course, elections are dynamic, and this election has seen more than its fair share of same-day registrants (not to mention an unknown number of voters moving from the inactive to active voter list).

While I applaud the Secretary of State’s office for their efforts at a top-down reporting of turnout, the grouping of both Third Party registered voters and Non-Partisans into a single Other category significantly obfuscates important distinctions in Nevada’s electorate.

And while I applaud the Secretary of State’s office for their efforts at a top-down reporting of turnout, there is one major issue with the data format they choose: the division of turnout data into Democrat, Republican, and Other. I think this significantly obfuscates important distinctions in voting behavior between Independent voters (those who support third parties) and Non-Partisans. And I think it is a problem that is seriously impacting Nevadans’ ability to understand what is going on in their elections.

But we will do our best. I want to start with the registration numbers. While the official turnout statistics use active voter registration as of Election Day, Tuesday, November 5th, these do not as the time of writing have the party breakdowns. But the regular monthly reports from the Secretary of States office does, so we can use those. I think they are close enough (the specifics are discussed a bit further below).

Not surprising, the three urban counties—Carson City, Clark, and Washoe—comprise just over 90% of all voters in Nevada, with the 14 rural counties containing 9.7%. And the Three Rurals breaking down consistent with other data: the Western Rural has about twice the voters as either the I-80 Corridor or the Central Rural.

At first glance, nothing on this table is very surprising. Distribution between the three major registration groups (Democrat, Republican, and Non-Partisan) is somewhat evenly split in the three urban counties. The 14 rural counties are now slightly majority Republican with very small Democrat minorities, and have fewer Non-Partisans as well.

Yet note the significant differences between the Three Rurals. The Western Rural and Central Rural regions look very similar, with only a slight difference in third-party voters (mostly IAP). But it is the I-80 Corridor (Elko, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, and Pershing) that has the largest percentage of registered Republicans (by almost 8%) and consequently a smaller percentage of Democrats and Non-Partisans. This strong Republican association is interesting beyond just policy issues. Remember that the I-80 Corridor is the youngest area of the state—and growing (see my article on the 2020 Census Data and Population Pyramids). They are bucking the trend towards younger areas having more non-partisans and are drifting more strongly Republican.

One other note on the Democrat-Republican split in the urban and rural counties. Over 95% of active registered Democrats live in Clark, Washoe, and Carson City, as opposed to less than 84% of Republicans. It is fair to say that with this disproportionate distribution, the Democrats have very little experience with rural Nevada—which shows in the election data.

I also have divided the Non-Partisans from the Third Party Voters (Independents is probably a better term). While Non-Partisans are the largest “party” in the state, they are not the outsized behemoth that much of the press coverage has made them out to be. Moreover, remember that Non-Partisan is the “default” category for voters automatically registered at the DMV but not choosing a specific party. As I argued in one of the Voting Population articles earlier this year, I suspect that a large portion of this group has no interest in politics and is simply unlikely to vote regardless of situation. The failure of Ballot Question # 3 (Ranked-Choice Voting and Open Primaries), whose Yes campaign focused heavily on Non-Partisans becoming involved, is proof of this.

But the reason for separating out the Third Party voters from Non-Partisan or “Other" is to show they actually are a fairly consistent presence across Nevada. Just over 7% of active Registered voters in Nevada are registered members of third parties, and the registration differences between urban counties (7.3%) and rural counties (7.6%) are negligible. There is some variation between the Three Rurals, going from a low to 6.8% in the I-80 Corridor to 7.6% in the Western Rural to a high of 8.4% in the Central Rural counties. Almost 10% of Esmeralda’s and Nye’s voters are third party—granted still a small number of voters overall.

And it should be noted that the Independent American Party is the largest single third party, accounting for 62% of all Independent (registered third party) voters. That figure translates into 4.5% of active registered voters statewide and at 5% in the Three Rurals (ranging from 4.5% in the I-80 Corridor to 5.7% in the Central Rural). Again, very consistent across the state. It is not as if the IAP is solely a rural phenomenon in Nevada.

Voter Turnout in the 2024 Election

So what does this mean for turnout? Here the Secretary of State’s various data reports present an issue (see the 2024 Election Turnout page for the various reports). First, the current daily reports are not really tied to the registration totals; they report the total registered voters as a proportion of all ballots cast, not as percent of party turnout which is what we need to understand. Furthermore, the reports use the Other category to report registration, which conflates Non-Partisans and Third Party voters together (apothetically as “not Democrat or Republican”).

One report, the new “State Voter Ballot Status Report,” does provide updated registration and voting data—at least for everything except Clark County. So much for a top-down unified system. It also is the “raw” data, so some information may change as same-day registrations or provisional ballots are checked and verified. Still, it is the most up-to-date information I have, even if differs from the “General Unofficial Turnout Report” so far by not taking updated registrations into account. For the record, I am using the report generated on Friday, November 8th at 1159 pm for the data below, for those of you who are playing along at home.

I am only looking at the 14 rural counties, since the absence of Clark County makes the data useless for urban-rural or state-level analysis. Compared to the registration data from November 1st used above, the 14 rural counties had an increase of almost 7,000 new voters—about 3.5%. The I-80 Corridor saw the largest increase of 2,958 voters (about 6.9%), while the Western Rural counties only increased 1,851 (1.7%). Most importantly, the increase was fairly evenly divided among all parties, with Non-Partisans and Third Parties registering slightly higher percentages of new voters. In the end, the registration percentages have not changed from the beginning of November.

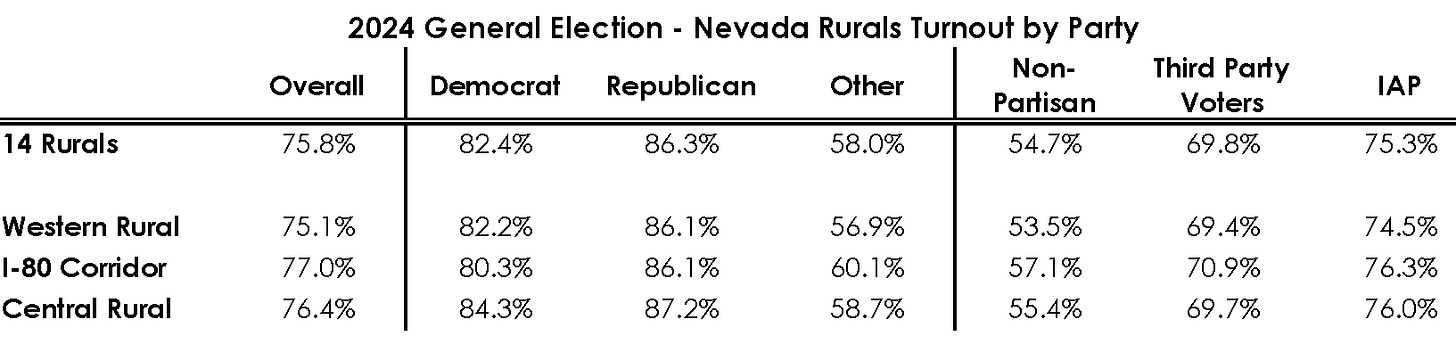

That said, the 14 rural counties posted an overall turnout of 75.8%, which is about 10% higher than the three urban counties. This over-voting tendency of the rurals has been consistent since at least 1984, and is hardly new. It is why the rurals can sway races even if they do not have the majority of votes to win them on their own.

What is interesting is what happens once the registration of voters is considered. Unsurprisingly, Republicans posted very high turnout numbers, over 86% across the Three Rurals. Democrats did not underperform either, over 80% across the board, even in the unfavorable I-80 Corridor counties. The major parties’ efforts to get out the vote worked.

Which brings us to the Non-Partisans and Third Parties. When grouped as the “Other” category that the Secretary of State’s office likes to use, the turnout is down—generally at least 17 points lower than county averages and over 20% lower than the major parties. That is a significant difference by itself.

The Other turnout category hides a major fact. Those registered with Third Parties turn out to vote. Non-Partisans? Not so much.

But digging down further, there is a more striking issue. Voters that align themselves with Third Parties have turnout levels only about 10-12% lower than the major parties. The IAP comes closer, within single digits difference between themselves and the Democrats and Republicans. In other words, those registered with third parties turnout to vote. Non-partisans? Not so much.

I would argue this should have serious repercussions on electoral policy issues. Nevada’s current automatic registration system is making it appear there is a large-scale rejection of party registration. Turnout during elections indicates this is not the case.

Senate Races and Third Parties. Or Not.

Turnout is not the same as votes, which is what elections are ultimately about. While the turnout is fairly in line with expectations (well, my expectations, at least), the actual voting did produce some perplexing situations.

We can start with our baseline—the presidential election. It came as a surprise to no one that Trump carried the rural counties. Indeed, over 15% of his vote total came from them. He even won Carson City (technically rural) by 11.5%, still more than 20% less than second lowest margin in Douglas County at 32.7%. Trump did lose both Clark County (by 2.8%) and Washoe County (by a scant 0.1% so far). But the rural margins of over 45% overall and 57.5% in the I-80 Corridor was enough to give him a comfortable 3.2% margin and, perhaps more significantly, a 50.6% majority of Nevada’s vote.

Down ballot, things look much different. Or, I should say, less surprising. Not one congressional seat in Nevada was flipped, and the Republicans failed to perform as well in the state legislative races as many had predicted (although they also avoided falling into supra-minority status). This pattern is something noticed by many in the primaries: Trump does not seem to have strong coattails to carry other candidates with him. Nowhere was this failure more disappointing than the U.S. Senate race.

While Trump won Nevada by a comfortable 3.2% margin, Republican Senate candidate Sam Brown lost by about 1.5%. Moreover, even in the 14 rural counties he carried by large margins he trailed the Republican presidential candidate by almost the exact same 5% margin. On the Democrat side, incumbent Senator Jacky Rosen posted almost the exact same vote totals as the Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris: Harris won 47.5% of Nevada’s vote, Rosen 47.9%.

What has sparked the Republican “blame the voters” narrative is trying to figure out what happened. Brown scored over 70,000 fewer votes than Trump—almost 23 times the loss of votes Rosen had compared to Harris (about 3,100). Given the tight margins, there were not many Trump for President-Rosen for Senate voters. So where did these presumably Republican voters go?

One possibility is that significant numbers of voters only voted for president and ignored the other races. To be honest, this fear was one that I held over the last few weeks. Yet that does not appear to have been the case. As of Sunday, November 10th, there were just over 18,600 fewer votes (about 1.3%) in the Senate race than in the presidential. That is smaller than the 21,400 vote margin in the race, and anyway there is no guarantee these were all Republican voters. And the only county which had more than 1% decrease in senate votes was Clark County at 1.5%—which is the only reason the overall total is so high. No votes were not the issue.

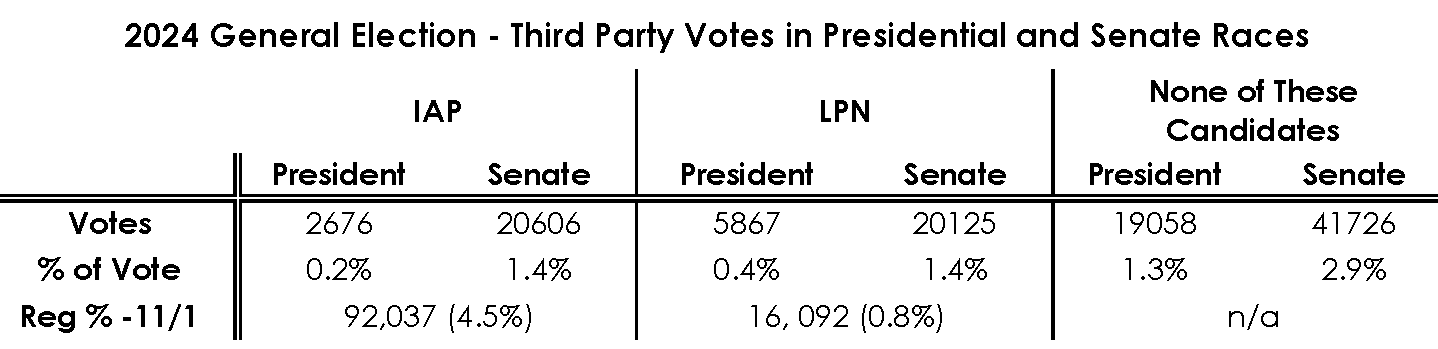

Hence the focus of third parties, especially the IAP and its Senate candidate Janine Hansen. The argument is that voters who went for Trump then split their votes down ballot. The prima facie evidence is that the IAP senate vote total of over 20,600 was ten times the total for their presidential candidate (the IAP ticket got just under 2700 votes for president state-wide). That ignores that the other major third party, the Libertarian Party of Nevada (LPN), also saw their vote total jump in the Senate race, from 5.800 in the presidential to just over 20,100. Even the perennial political bride’s maid of “None of These Candidates” more than doubled in the Senate race.

Looking at the data is illustrative in this case. The table below gives the percentages of total votes for these three groups (IAP, LPN, and None of These Candidates) in both the presidential and senate elections.

Individually, the Third Parties are not wholly responsible for Brown’s drop in votes. Neither the IAP nor the LPN could have provided the vote margin even if they had broken 100% for Brown—which was never likely. The LPN actually exceeded their pre-election registration totals, but even that would not have been enough.

In fact, Brown likely benefitted from the IAP. Note that as discussed above the IAP comprises 4.5% of all voters in Nevada, and had an election turnout of about 76%. Those numbers translate into a share of the ballots cast to 3.4%, roughly. That is 2 points higher than voted for Janine Hansen. I suspect that a number of IAP voters actually broke for Sam Brown much the same way they broke for Trump. In other words, the IAP underperformed significantly.

The one outlier is the None of These Candidates. While the vote total would have been enough to help Brown, I highly suspect that those voters who voted “None of These Candidates” in the presidential likely did so in the Senate race as well. Taking that group into account does bring to total to about equal to Rosen’s margin of victory. I am not convinced those are all Republican voters, however. I doubt that these voters would have been enough either.

In short, it would have taken a combination of votes from various sources to give Sam Brown the Senate race.

Conclusions: The Imperial Presidency Obsession

The truth is that Sam Brown lost because voters, particularly on the political right, find it far easier to spread their votes around (or not vote at all) on down ballot races compared to the presidential election. For third parties, this makes a lot of sense; it is a primary way for them to gain influence by winning elections. But the number of “None of These Candidate” voters is something else entirely. But the more I look at these numbers, I am convinced that we are seeing a popularization of the “imperial presidency” theory on the right side of the political spectrum

The concept of the imperial presidency was initially stated by famed historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. in his 1973 work of the same title (Wikipedia has a decent entry on the book for those wanting the basics). Schlesinger’s concern at the time—in the midst of Watergate—was how the Cold War had allowed the president to assume enlarged powers related to foreign policy that had strengthened the office is potentially dangerous ways including usurping key powers from the Legislative Branch. Since its publication, the idea of the imperial presidency has become a leading theory in understanding the apparent growth of power in the executive since the 1960s which appears to be accelerating in the twenty-first century.

Central to the theory is the absence of congressional counter-balance to the accumulating powers of the executive, which is theoretically how the U.S. Constitution should work. The question of what powers Congress should or should not give the executive branch and when to push back is an important one, but beyond the scope of this piece. But I do think the frequent discussion of the imperial presidency has an impact on how voters think about the value of their votes.

Simply put, if the presidency is the one all-powerful office, the lower offices—particularly congressional offices like Senate—do not really have the same importance. Therefore, votes can be given to third parties or “None of These Candidates” without seriously impacting the outcome. Unfortunately, the Republican Party has done little to correct voters beliefs here over the last few election cycles. They have tended to put significant support only into the presidential races (especially in the Trump era), on the assumption that presidential votes will carry down ballot. What it appears to be doing is marshalling third party votes for Republican presidential candidates then leaving the field open to Democratic candidates farther down the ballot.

Although Sam Brown’s campaign is under a lot fire now (some deserved, some not), a bigger issue is that Republicans and especially Republican candidates need to spend more time talking to voters as to why the down ballot races matter to Republican success. Despite the imperial presidency model, Congress still is vital. Presidents are still very constrained without policy allies in the legislature.

The Democrats know this, which is why they are losing far less votes down ballot. Of course, they have also been far more aggressive in keeping left-leaning third parties off of ballots (see the Greens under Jill Stein and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. this election cycle). This approach is wrong as well, and I can only hope Republicans do not try to emulate Democrats in that approach.

One final election note: the Secretary of State expressed frustration earlier last week concerning the slowness of getting votes counted, mainly due to the long lag in accepting mail ballots. Join the club. His office is also embroiled in a series of controversies, some frivolous but others legitimate, concerning voting rolls. I will point out that since 2020 (and here I mean pre-pandemic) the state of Nevada effectively has farmed out two major parts of election operations—voter registration at the DMV and ballot delivery to the USPS—to agencies that DO NOT have elections as their primary duties and do not have mechanisms of accountability to correct issues. I am not convinced fine-tuning the requirements are the answer; a re-think of this entire arrangement is in order.